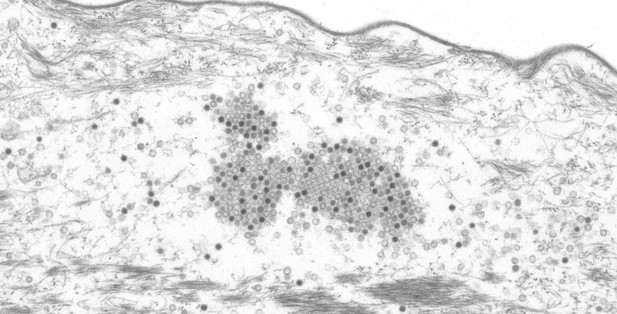

MnPV papillomaviruses in the skin of a Southern multimammate mouse. Image credit: Michelle Neßling, DKFZ Core Facility EM (CC BY 4.0)

Cancer is not one disease but rather a collection of disorders. As such there are many reasons why someone may develop cancer during their lifetime, including the individual’s family history, lifestyle and habits. Infections with certain viruses can also lead to cancer and human papillomaviruses are viruses that establish long-term infections that may result in cancers including cervical and anal cancer, and the most common form of cancer worldwide, non-melanoma skin cancer.

The human papillomavirus, or HPV for short, is made up of DNA surrounded by a protective shell, which contains many repeats of a protein called L1. These L1 proteins stick to the surfaces of human cells, allowing the virus to get access inside, where it can replicate before spreading to new cells. The immune system responds strongly to HPV infections by releasing antibodies that latch onto L1 proteins. It was therefore not clear how HPV could establish the long-term infections and cause cancer when it was seeming being recognized by the immune system.

Now, Fu et al. have used the Southern multimammate mouse, Mastomys coucha, as a model system for an HPV infection to uncover how papillomaviruses can avoid the immune response. This African rodent is naturally infected with a skin papillomavirus called MnPV which, like its counterpart in humans, can trigger the formation of skin warts and malignant skin tumors.

Fu et al. took blood samples from animals that had been infected with the virus over a period of 76 weeks to monitor their immune response overtime. This revealed that, in the early stages of infection, the virus made longer-than-normal versions of the L1 protein. Further analysis showed that these proteins could not form the virus’s protective shell but could trigger the animals to produce antibodies against them. Fu et al. went on to show that the antibodies that recognized the longer variants of L1 protein where “non-neutralizing”, meaning that could not block the spread of the virus, which is a prerequisite for immunity. It was only after a delay of four months that the animals started making neutralizing antibodies that were directed against the shorter L1 proteins that actually makes up the virus’s protective coat.

These findings suggest that virus initially uses the longer version of the L1 protein as a decoy to circumvent the attention of the immune system and provide itself with enough time to establish an infection. The findings also have implications for other studies that have sought to assess the success of an immune response during a papillomavirus infection. Specifically, the delayed production of the neutralizing antibodies means that their presence does not necessarily indicate that a patient is not already infected by a papillomavirus that in the future may cause cancer.