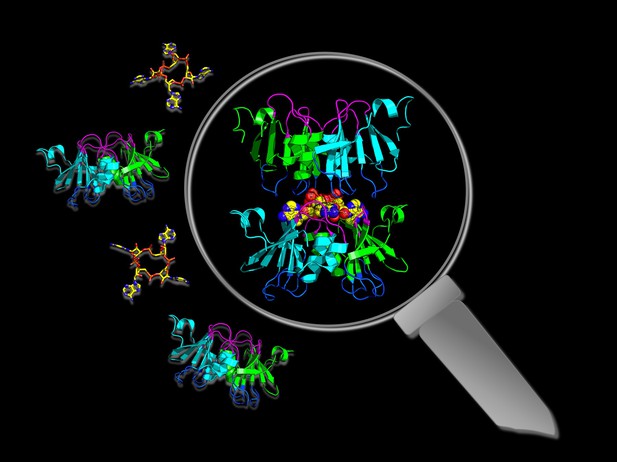

Two Csx3 ring nucleases can come together to form a structure that helps to destroy cOA molecules. Image credit: Athukoralage et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Bacteria protect themselves from infections using a system called CRISPR-Cas, which helps the cells to detect and destroy invading threats. The type III CRISPR-Cas system, in particular, is one of the most widespread and efficient at killing viruses.

When a bacterium is infected, the CRISPR-Cas system takes a fragment of the genetic material of the virus, and copies it into a molecule. These molecular ‘police mugshots’ are then loaded into a complex of Cas proteins that patrol the cell, looking for a match and destroying any virus that can be identified.

Some Cas proteins also produce alarm signals, called cyclic oligoadenylates (cOAs), which can trigger additional defences. However, this process can damage the genetic material of the bacterium, harming or even killing the cell.

Enzymes known as ring nucleases can promptly degrade cOAs and turn off this defence system before it causes harm. However, ring nucleases have only been found in a few species to date; how most bacteria deal with cOA toxicity has remained unknown. Here, Athukoralage et al. set out to determine whether a widespread enzyme known as Csx3, which is often associated with type III CRISPR-Cas systems, could be an alternative off switch for cOA triggered defences.

Initial ‘test tube’ experiments with purified Csx3 proteins confirmed that the enzyme could indeed break down cOAs. A careful dissection of Csx3’s molecular structure, using biochemical and biophysical techniques, revealed that it worked by ‘sandwiching’ a cOA molecule between two co-operating portions of the enzyme. As a final test, Csx3 was introduced into strains of bacteria genetically engineered to have a fully functional Type III CRISPR-Cas system. In these cells, Csx3 successfully turned off the Type III immune response.

These results reveal a new way that bacteria avoid the toxic side effects of their own immune defences. Ultimately, this could pave the way for the development of anti-bacterial drugs that work by blocking Csx3 or similar proteins.