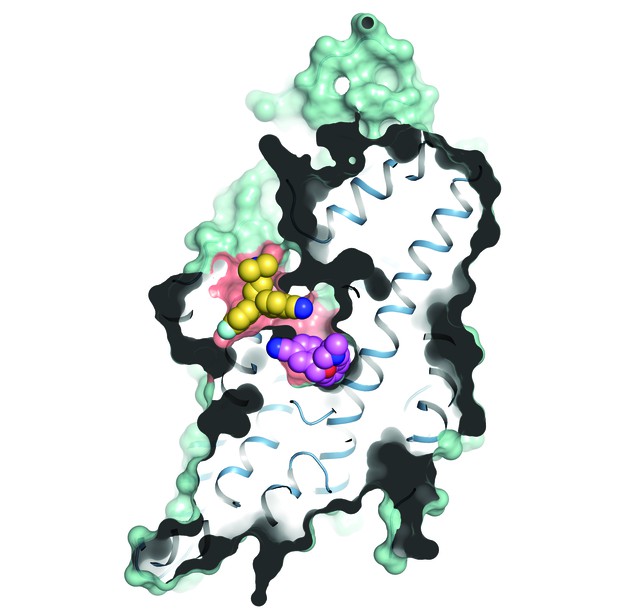

Slice through a human serotonin transporter structure illustrating the binding sites (in purple and yellow) of a type of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Image credit: Jonathan A. Coleman, Evan M. Green, and Eric Gouaux, Oregon Health and Science University (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Serotonin is perhaps best known as a chemical messenger in the brain, where it regulates mood, appetite and sleep. But as a hormone, serotonin works in other parts of the body too. Serotonin is predominantly made in the gut, where it binds receptor proteins that help to regulate the movement of substances through the gastrointestinal tract, aiding digestion. However, a surge in serotonin release in the gut induces vomiting and nausea, which commonly happens as a side effect of treating cancer with radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Anti-nausea drugs used to manage and prevent the severe nausea and vomiting experienced by cancer patients are therefore designed to target serotonin receptors in the gut. These drugs, called setrons, work by binding to serotonin receptors before serotonin does, essentially neutralising the effect of any surplus serotonin. Although they generally target serotonin receptors in the same way, some setrons are more efficient than others and can provide longer lasting relief. Clarifying exactly how each drug interacts with its target receptor might help to explain their differential effects.

Basak et al. used a technique called cryo-electron microscopy to examine the interactions between three common anti-nausea drugs (palonosetron, ondansetron and alosetron) and one type of serotonin receptor, 5-HT3AR. The experiments showed that each drug changed the shape of 5-HT3AR, thereby inhibiting its activity to varying degrees. Further analysis identified a distinct ‘interaction fingerprint’ for the three setron drugs studied, showing which of the receptors’ subunits each drug binds to. Simulations of their interactions also showed that water molecules play a crucial role in the process, exposing the binding pocket on the receptor’s surface where the drugs attach.

This work provides a structural blueprint of the interactions between anti-nausea drugs and serotonin receptors. The structures could guide the development of new and improved therapies to treat nausea and vomiting brought on by cancer treatments.