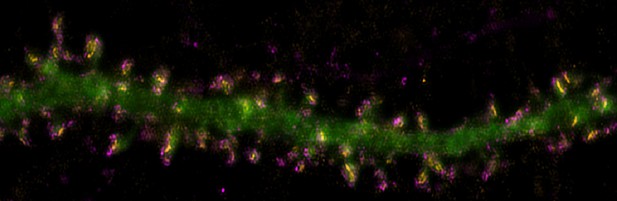

Image of a nerve cell in the direct pathway (green) that contains a mutated version of LRRK2, showing the receptor proteins that regulate the connections between nerve cells (purple) organized in to distinct domains (orange). Image credit: Chuyu Chen (CC BY 4.0)

Parkinson’s disease is caused by progressive damage to regions of the brain that regulate movement. This leads to a loss in nerve cells that produce a signaling molecule called dopamine, and causes patients to experience shakiness, slow movement and stiffness. When dopamine is released, it travels to a part of the brain known as the striatum, where it is received by cells called spiny projection neurons (SPNs), which are rich in a protein called LRRK2. Mutations in this protein have been shown to cause the motor impairments associated with Parkinson’s disease.

SPNs send signals to other regions of the brain either via a ‘direct’ route, which promotes movement, or an ‘indirect’ route, which suppresses movement. Previous studies suggest that mutations in the gene for LRRK2 influence the activity of these pathways even before dopamine signaling has been lost. Yet, it remained unclear how different mutations independently affected each pathway. To investigate this further, Chen et al. studied two of the mutations most commonly found in the human gene for LRRK2, known as G2019S and R1441C. This involved introducing one of these mutations in to the genetic code of mice, and using fluorescent proteins to mark single SPNs in either the direct or indirect pathway.

The experiments showed that both mutations disrupted the connections between SPNs in the direct and indirect pathway, which altered the activity of nerve cells in the striatum. Chen et al. found that individual connections were more strongly affected by the R1441C mutation. Further experiments showed that this was caused by the re-organization of a receptor protein in the nerve cells of the direct pathway, which increased how SPNs responded to inputs from other nerve cells.

These findings suggest that LRRK2 mutations disrupt neural activity in the striatum before dopamine levels become depleted. This discovery could help researchers identify new therapies for treating the early stages of Parkinson’s disease before the symptoms of dopamine loss arise.