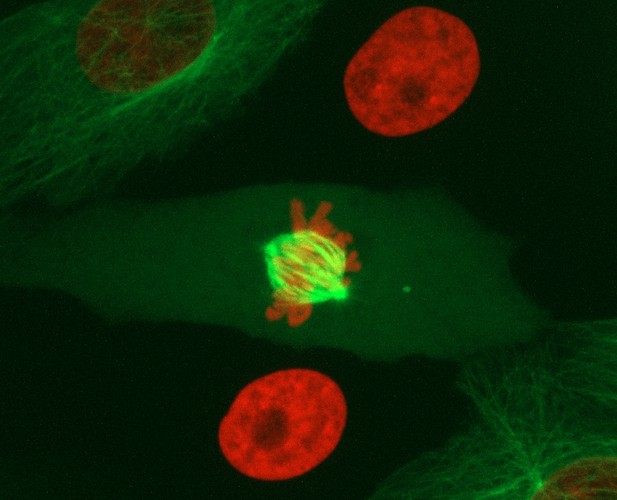

Cell dividing, with the DNA shown in red. Image credit: Zeiss Microscopy (CC BY 2.0)

New cells are made when a single cell duplicates its DNA and divides into two cells, distributing the DNA equally between them, in a process called mitosis. The splitting of the two copies of DNA happens through a series of controlled events known as mitotic exit. Previous research has suggested that mitotic exit relies on both the destruction of specific proteins and the removal of tags called phosphate groups from other proteins. Phosphate groups modify how proteins behave and their removal can trigger changes in a protein’s activity.

Although protein destruction and phosphate group removal were known to be important to mitotic exit, it was not understood how they are coordinated in the cell to ensure the correct order of events. Holder et al. have used a technique called mass spectrometry to monitor the level of thousands of proteins, and any tags attached to them, during mitotic exit in human cells grown in the laboratory.

The experiments revealed that the destruction of a single protein, known as cyclin B, plays a major role in triggering subsequent events. The removal of cyclin B activates enzymes known as phosphatases, which remove phosphate groups from proteins. Phosphatases then act on a wide range of proteins in a specific order that depends on the environment surrounding the phosphate group. This ‘chain’ of phosphatase activity determines the order of events during mitotic exit.

The findings of Holder et al. contribute to the basic understanding of how mitotic exit works. Errors in the process can affect the stability of a cell’s genome, contributing to diseases such as cancer. In the future, this may help to identify what goes wrong in these cases and potential avenues for developing treatments.