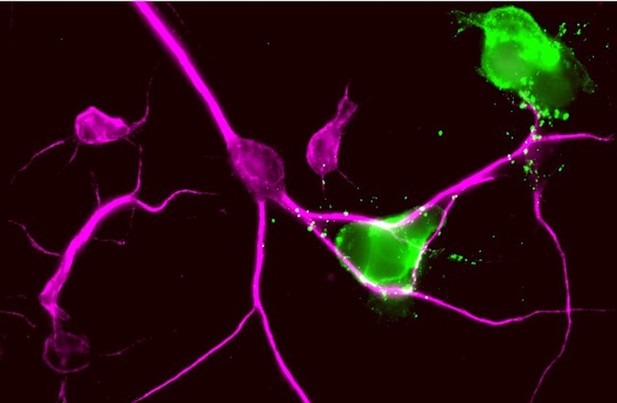

Cancer cells (green) which carry GFP send granules containing the molecule into neurons (purple) cultured in the same environment. Image credit: Tang et al. (CC BY 4.0)

It takes the coordinated effort of more than 40 trillion cells to build and maintain a human body. This intricate process relies on cells being able to communicate across long distances, but also with their immediate neighbors. Interactions between cells in close contact are key in both health and disease, yet tracing these connections efficiently and accurately remains challenging.

The surface of a cell is studded with proteins that interact with the environment, including with the proteins on neighboring cells. Using genetic engineering, it is possible to construct surface proteins that carry a fluorescent tag called green fluorescent protein (or GFP), which could help to track physical interactions between cells.

Here, Tang et al. test this idea by developing a new technology named GFP-based Touching Nexus, or G-baToN for short. Sender cells carry a GFP protein tethered to their surface, while receiver cells present a synthetic element that recognizes that GFP. When the cells touch, the sender passes its GFP to the receiver, and these labelled receiver cells become ‘green’.

Using this system, Tang et al. recorded physical contacts between a variety of human and mouse cells. Interactions involving more than two cells could also be detected by using different colors of fluorescent tags. Furthermore, Tang et al. showed that, alongside GFP, G-baToN could pass molecular cargo such as proteins, DNA, and other chemicals to receiver cells.

This new system could help to study interactions among many different cell types. Changes in cell-to-cell contacts are a feature of diverse human diseases, including cancer. Tracking these interactions therefore could unravel new information about how cancer cells interact with their environment.