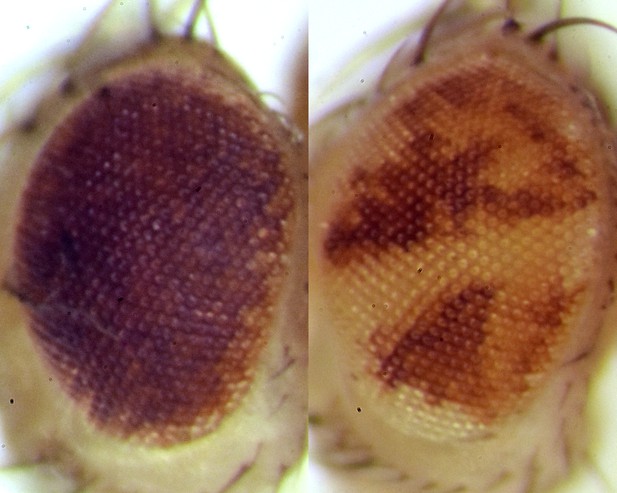

Fruit flies eyes in which aneuploid cells (unpigmented) have been induced. On the right, healthy cells have been further modified to not be able to kill their neighbors. In this case, aneuploid cells survive and multiply. On the left, aneuploid cells have been eliminated through competition. Image credit: Nicholas E Baker (CC BY 4.0)

Aneuploid cells emerge when cellular division goes awry and a cell ends up with the wrong number of chromosomes, the tiny genetic structures carrying the instructions that control life’s processes. Aneuploidy can lead to fatal conditions during development, and to cancer in an adult organism.

A safety mechanism may exist that helps the body to detect and remove these cells. Yet, exactly this happens is still poorly understood: in particular, it is unclear how cells manage to ‘count’ their chromosomes.

One way they could do so is through the ribosomes, the molecular ‘factories’ that create the building blocks required for life. In a cell, every chromosome carries genes that code for the proteins (known as Rps) forming ribosomes. Aneuploidy will alter the number of Rp genes, and in turn the amount and type of Rps the cell produces, so that ribosomes and the genes for Rps could act as a ‘readout’ of aneuploidy. Ji et al set out to test this theory in fruit flies.

The first experiment used a genetic manipulation technique called site-specific recombination to remove parts of chromosomes from cells in the developing eye and wing. Cells which retained all their Rp genes survived, while those that were missing some usually died – but only when the surrounding cells were normal. In this situation, healthy cells eliminated their damaged neighbours through a process known as cell competition. A second experiment, using radiation as an alternative method of damaging chromosomes, also gave similar results.

The work by Ji et al. reveals how the body can detect and eliminate aneuploid cells, potentially before they can cause harm. If the same mechanism applies in humans, boosting cell competition may, one day, helps to combat diseases like cancer.