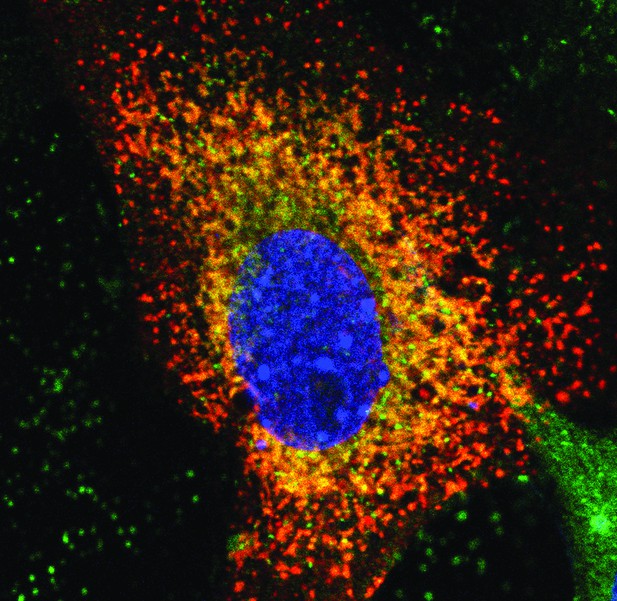

Image of a mouse osteoblast cell producing the precursor for the hormone osteocalcin (red), which is cut by an enzyme (shown in green). At the same time, a sugar group is attached to osteocalcin, which makes the hormone more stable when it is released into the blood. Image credit: Omar Al Rifai (CC BY 4.0)

Bones provide support and protection for organs in the body. However, over the last 15 years researchers have discovered that bones also release chemicals known as hormones, which can travel to other parts of the body and cause an effect. The cells responsible for making bone, known as osteoblasts, produce a hormone called osteocalcin which communicates with a number of different organs, including the pancreas and brain.

When osteocalcin reaches the pancreas, it promotes the release of another hormone called insulin which helps regulate the levels of sugar in the blood. Osteocalcin also travels to other organs such as muscle, where it helps to degrade fats and sugars that can be converted into energy. It also has beneficial effects on the brain, and has been shown to aid memory and reduce depression.

Osteocalcin has largely been studied in mice where levels are five to ten times higher than in humans. But it is unclear why this difference exists or how it alters the role of osteocalcin in humans. To answer this question, Al Rifai et al. used a range of experimental techniques to compare the structure and activity of osteocalcin in mice and humans.

The experiments showed that mouse osteocalcin has a group of sugars attached to its protein structure, which prevent the hormone from being degraded by an enzyme in the blood. Human osteocalcin has a slightly different protein sequence and is therefore unable to bind to this sugar group. As a result, the osteocalcin molecules in humans are less stable and cannot last as long in the blood. Al Rifai et al. showed that when human osteocalcin was modified so the sugar group could attach, the hormone was able to stick around for much longer and reach higher levels when added to blood in the laboratory.

These findings show how osteocalcin differs between human and mice. Understanding this difference is important as the effects of osteocalcin mean this hormone can be used to treat diabetes and brain disorders. Furthermore, the results reveal how the stability of osteocalcin could be improved in humans, which could potentially enhance its therapeutic effect.