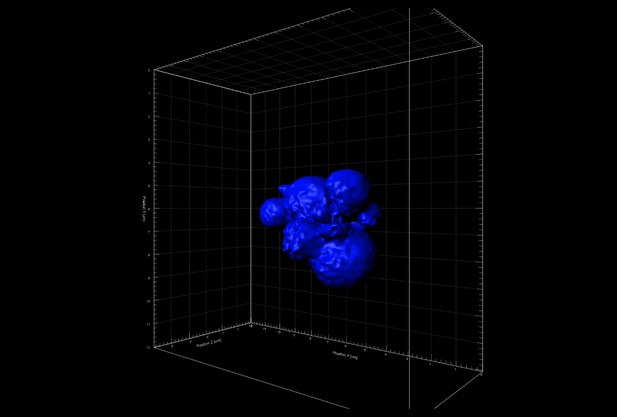

Lipid droplets (orange) in zebrafish cells. Image credit: Lumaquin, Johns et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Organisms need fat molecules as a source of energy and as building blocks, but these ‘lipids’ can also damage cells if they are present in large amounts. Cells guard against such toxicity by safely sequestering lipids in specialized droplets that participate in a range of biological processes. For instance, these structures can quickly change size to store or release lipids depending on the energy demands of a cell.

It is possible to image lipid droplets – using, for example, dyes that preferentially stain fat – but often these methods can only yield a snapshot: tracking lipid droplet dynamics over time remains difficult. Lumaquin, Johns et al. therefore set out to develop a new method that could label lipid droplets and monitor their behaviour ‘live’ in the cells of small, transparent zebrafish larvae.

First, the fish were genetically manipulated so that a key protein found in lipid droplets would carry a fluorescent tag: this made the structures strongly fluorescent and easy to track over time. And indeed, Lumaquin, Johns et al. could monitor changes in the droplets depending on the fish diet, with the structures getting bigger when the animal received rich food, and shrinking when resources were scarce. Finally, experiments were conducted to screen for compounds that could lead to lipids being released in fat cells. The new imaging technique was then used to confirm the effect of these molecules in live cells, revealing an unexpected role for a signalling molecule known as nitric oxide, which also turned out to be regulating lipid droplets in cancerous cells. Further work then showed that drugs affecting nitric oxide could modulate lipid droplet size in both normal and tumor cells.

This work has validated a new method to study the real-time behavior of lipid droplets and their responses to different stimuli in living cells. In the future, Lumaquin, Johns et al. hope that the technique will help to shed new light on how lipids are involved in both healthy and abnormal biological processes.