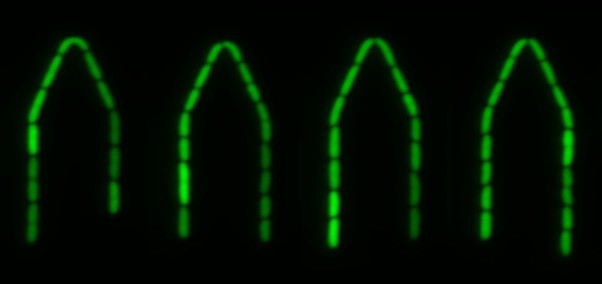

Experimental set-up to track daughter cells, with a cell trap that holds a mother cell at the tip, as daughter cells are pushed down the sides. Image credit: Vashistha, Kohram and Salman (CC BY 4.0)

All the different forms of life on our planet – including animals, plants, fungi and bacteria – tend to grow, multiply and expand. This happens through a process called cell division, where one cell becomes two; two cells become four; four cells become eight; and so on. Each dividing cell passes on the same set of genetic instructions to its two daughter cells in the form of DNA. Its remaining contents, made up of a mixture of proteins, RNA and other chemicals, also get divided up equally between the two new cells.

This division of cellular assets establishes a form of 'cellular memory', where daughter cells retain very similar properties to their ancestors, which helps them remain stable over time. Yet this memory can fade, and small changes in how a cell looks or acts can appear over many generations of cell division. This happens even when the exact same set of DNA-based genetic instructions have been passed down to daughter cells, confirming that other factors aside from DNA do influence cellular properties and can act to maintain them or introduce variation over time.

Here, Vashistha, Kohram and Salman set out to understand how long cellular memory could be maintained in dividing E. coli bacteria. To do this, they created a technique to track cellular memory as it passed down from a single mother cell to two daughter cells over dozens of generations. Using this technique, Vashistha, Kohram and Salman found that some inherited elements, including cell size and the time cells took to divide, were maintained between mother and daughter cells for almost 10 generations. Other elements, such as the density of proteins inside each cell, started changing almost immediately after daughter cells were formed, and only remained similar for about two generations.

These findings suggest that cellular memory may be long, but is not infinite, and that inheritance of non-genetic elements can help maintain cellular memory and reduce variation among new-born cells for considerable number of generations. Building on this research to achieve a better understanding of cellular memory may allow researchers to harness these insights to direct the evolution of different cellular properties over time. This could have a wide range of potential applications, such as designing new infection control measures for viruses or bacteria; enhancing our ability to grow working organs for tissue transplant; or improving the texture and consistency of cultured, lab-grown meat.