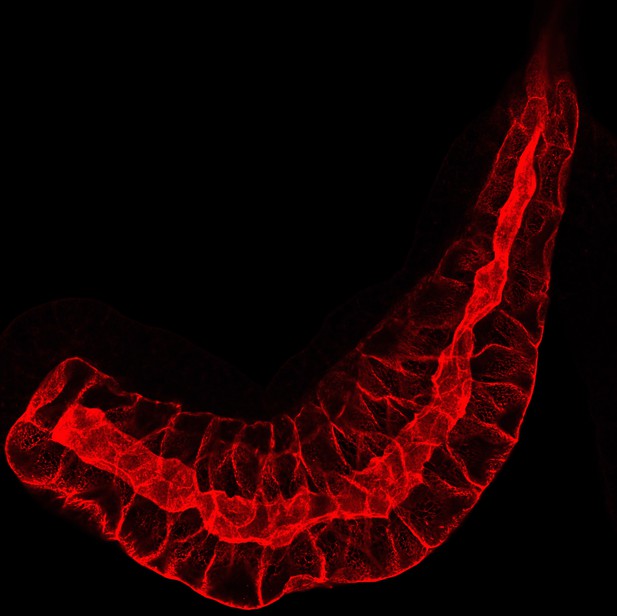

Microscopy image of a healthy salivary gland from a fruit fly larva. Image credit: Dilan Khalili (CC BY 4.0)

Tissues and organs work hard to maintain balance in everything from taking up nutrients to controlling their growth. Ageing, wounding, sickness, and changes in the genetic code can all alter this balance, and cause the tissue or organ to lose some of its cells. Many tissues restore this loss by dividing their remaining cells to fill in the gaps. But some – like the salivary glands of fruit fly larvae – have lost this ability.

Tissues like these rely on being able to sense and counteract problems as they arise so as to not lose their balance in the first place. The immune system and stress responses are crucial for this process. They trigger steps to correct the problem and interact with each other to find a common decision about the fate of the affected tissue. To better understand how the immune system and stress response work together, Krautz, Khalili and Theopold genetically manipulated cells in the salivary gland of fruit fly larvae. These modifications switched on signals that stimulate cells to keep growing, causing the salivary gland’s tissue to slowly lose its balance and trigger the stress and immune response.

The experiments showed that while the stress response instructed the cells in the gland to die, a peptide released by the immune system called Drosomycin blocked this response and prevented the tissue from collapsing. The cells in the part of the gland not producing this immune peptide were consequently killed by the stress response. When all the cells in the salivary gland were forced to produce Drosomycin, none of the cells died and the whole tissue survived. But it also allowed the cells in the gland to grow uncontrollably, like a tumor, threatening the health of the entire organism.

Mapping the interactions between immune and stress pathways could help to fine-tune treatments that can prevent tissue damage. Fruit flies share many genetic features and molecular pathways with humans. So, the next step towards these kinds of treatments would be to screen for similar mechanisms that block stress activation in damaged human tissues. But this research carries a warning: careless activation of the immune system to protect stressed tissues could lead to uncontrolled tissue growth, and might cause more harm than good.