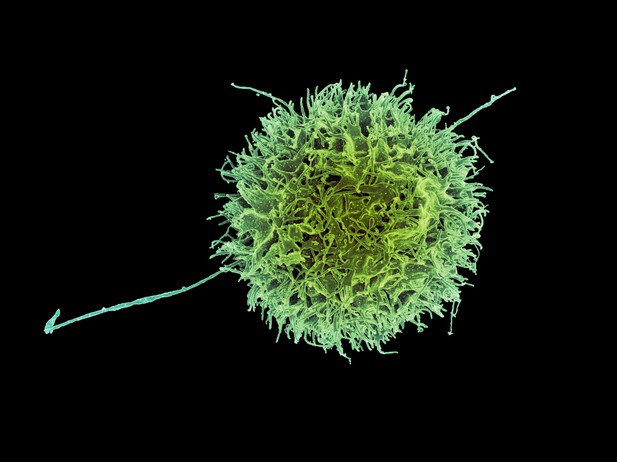

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a natural killer cell from a human donor. Image credit: NIAID (CC BY 2.0)

Cells are the building blocks of all living organisms. They come in many types, each with a different role. Understanding the composition of cells, i.e., how many cells and which types of cells are present inside an organ can indicate what that organ does. It can also reveal how that organ changes under different conditions, like during an infection or treatment.

The most powerful methods for studying cells work well for species researchers already know a lot about, such as mice, zebrafish or humans, but not for less studied animals. To change this Accorsi, Box, Peuß et al. created a new tool called Image3C to be used for studying the composition of cells in less researched organisms.

Instead of using reagents that only work for specific species, the tool uses molecules that work across many species, like dyes that stain the cell nucleus. A cell-sorting machine, known as a flow cytometer, connected to a microscope then takes pictures of hundreds of stained cells each second and Image3C groups them based on their appearance, without the need for any prior knowledge about the cell types. Accorsi et al. then tested Image3C on immune system cells of zebrafish, a well-studied animal, and apple snails, an under-studied animal. For both species, the tool was able to sort cells into groups representing different parts of the immune system.

Image3C speeds up the grouping process and reduces the need for user intervention and time. This lowers the risk of bias compared to manual counting of cells. It can sort cells even when the types of cells in an organism are unknown and even when specialized reagents for an organism do not exist. This means that it could characterise the cell make-up of new tissues coming from organisms never studied before. Access to this uncharted world of cells stands to reveal previously inaccessible clues about how organs behave and evolve and allow researchers to investigate the impact of environmental changes on these cells.