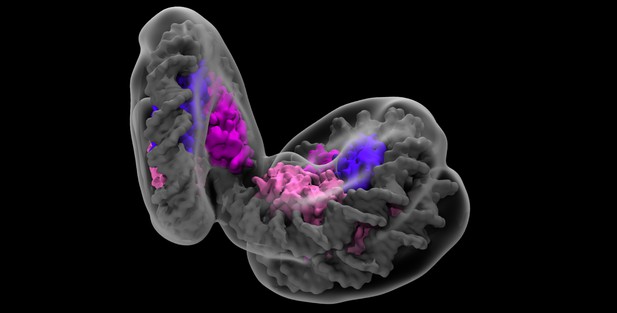

Archaeal DNA wrapped around a histone. Image credit: Sam Bowerman (CC BY 4.0)

All animals, plants and fungi belong to a group of living organisms called eukaryotes. The two other groups are bacteria and archaea, which include unicellular, microscopic organisms. All three groups have genes, which are typically stored on long strands of DNA. Eukaryotes have so much DNA that they use proteins called histones to help package and organize it inside each cell. Archaea also have simplified histones that help store their DNA, and studying these proteins could reveal how eukaryotic histones first evolved.

In eukaryotes, groups of eight histones form a short cylinder that organizes a small section of DNA into a structure called a nucleosome. Each cell needs hundreds of thousands of nucleosomes to arrange its DNA. Eukaryotic cells also contain other proteins that release pieces of DNA from histones so that their genetic information can be used. The histones in Archaea don’t form discrete nucleosomes, instead, they coil DNA into ‘slinky-like’ shapes. It’s still unclear how DNA packing in archaea works and how it differs from eukaryotes.

Bowerman, Wereszczynski and Luger used computer simulations, biochemistry and cryo-electron microscopy to study the histones from archaea. The archaeal ‘slinky-like’ histone structures are more flexible than nucleosomes, and can open and close like clamshells. This flexibility allows the information in the genomes of Archaea to be easily accessed, so, unlike in eukaryotes, archaeal cells may not need other proteins to release the DNA from the histones.

The ability to package DNA allows cells to contain many more genes, so evolving histones was a vital step in the evolution of eukaryotic life, including the appearance of animals. Archaeal histones may reflect early versions of histones in eukaryotes, and can be used to understand how DNA packing has evolved. Furthermore, a greater understanding of Archaea may help better explain their role in health and global ecosystems, and allow their use in industrial applications.