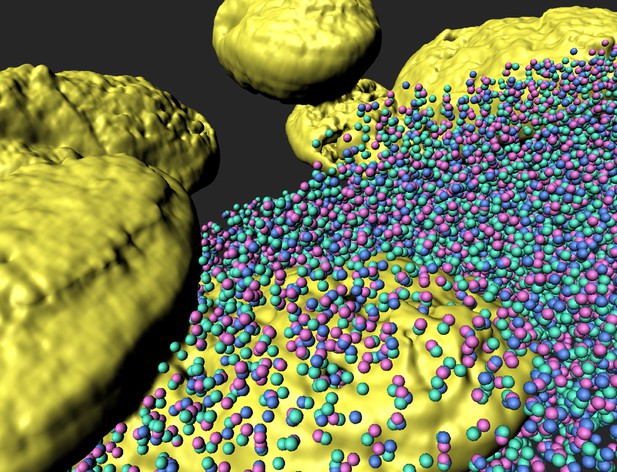

A 3D rendering of a cell infected with influenza, with individual viral RNA segments colored in teal, blue and magenta. Image credit: Jenny E. Jones (CC BY 4.0)

The viruses responsible for influenza evolve rapidly during infection. Changes typically emerge in two key ways: through random mutations in the genetic sequence of the virus, or by reassortment. Reassortment can occur when two or more strains infect the same cell. Once in a cell, viral particles ‘open up’ to release their genetic material so it can make copies of itself using the cell’s machinery. The new copies of the genetic material of the virus are used to make new viral particles, which then envelop the genetic material and are released from the cell to infect other cells. If several strains of a virus infect the same cell, a new viral particle may pick up genetic segments from each of the infecting strains, creating a new strain via reassortment.

Several factors are known to affect the success of the reassortment process. For example, if the new strain acquires a genetic defect that hinders its replication cycle, it is likely to die out quickly. Other times, this trading of genetic information can create a strain that is more resistant to the human immune system, allowing it to sweep across the globe and cause a deadly pandemic. However, a key part of the reassortment process that still remains unclear is how genome segments from two different influenza strains recognize each other before merging together to create hybrid daughter viruses.

To explore this further, Jones et al. used a technique called fluorescence microscopy. They found that genome segments that evolved along similar paths were more likely to cluster in the same area inside infected cells, and therefore, more likely to be reassorted together into a new strain during assembly of daughter viruses. This suggests that assembly may guide the evolutionary path taken by individual genomic segments. Jones et al. also looked at the evolution of different genome segments collected from patients suffering from seasonal influenza, and found that these segments had a distinct evolutionary path to those in pandemic-causing strains.

This research provides new insights into the role of reassortment in the evolution of influenza viruses during infection. In particular, it suggests that how the genome segments interact with one another may have a previously unknown and important role in guiding this evolution. These insights could be used to predict future reassortment events based on evolutionary relationships between influenza virus genomic segments, and may in the future be used as part of risk assessment tools to predict the emergence of new pandemic strains.