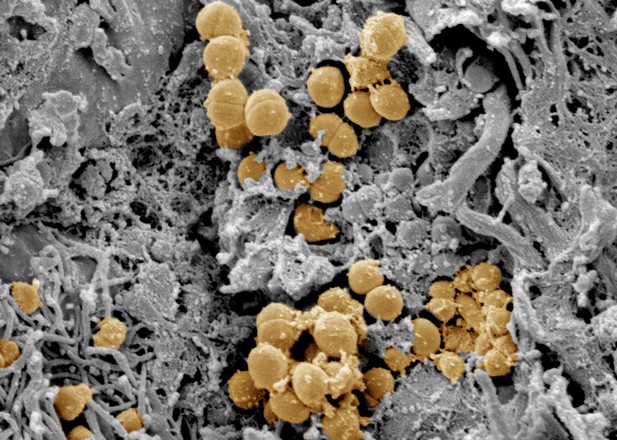

Staphylococcus aureus bacteria (yellow) collected from an infected wound. Image credit: Mariena van der Plas and Matthias Mörgelin (CC BY 4.0)

Infected wounds and burns represent a serious risk to patients: they can delay healing and, if left untreated, can lead to generalised infection or sepsis, organ failure and death. Wounds and burns get infected when harmful micro-organisms, such as bacteria, enter the wound. Predicting the risk of infections, and detecting them early, could reduce their impact and make treating them easier.

A way to distinguish between healing and infected wounds is to study how proteins are broken down in each situation. Proteases are the enzymes that break down proteins, and they are different in healing wounds and infected wounds that are failing to heal. This is because, while the body produces proteases, the bacteria that cause infection do so too. Each protease breaks down proteins in a specific way, resulting in a different set of protein fragments, known as peptides. Together, all the peptides in a wound are referred to as the wound’s ‘peptidome’. Studying the peptidome of a wound could show whether it is infected, and even what type of bacteria might be responsible, which could help identify suitable treatments.

Van der Plas et al. used a technique called mass spectrometry to study the peptidome of wounds after surgery. Sterile post-surgical wounds showed high levels of peptides compared to plasma, the liquid component of blood, with up to 4,300 different peptides. Comparing healing wounds to ones infected with the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus revealed that infected wounds contained peptides from about 150 proteins not found in uninfected wounds, while peptides from 90 proteins were unique to uninfected wounds. The peptides exclusive to uninfected wounds included some linked to antimicrobial activity and immune system activity.

Van der Plas et al.’s results suggest that analysing the peptidome may be an approach to tracking the healing status of wounds, making it easier to detect infection before symptoms are apparent. The next step will be to study more wounds and identify the reliable peptide markers to use them for diagnostic tests.