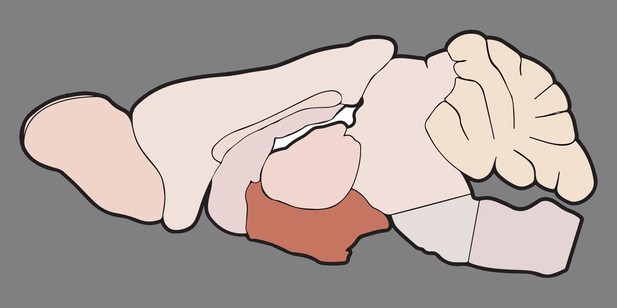

The mouse brain – hypothalamus highlighted in dark pink. Image credit: Adapted from Ann Kennedy (CC BY 4.0)

Colorectal (or ‘bowel’) cancer killed nearly a million people in 2018 alone: it is, in fact, the second leading cause of cancer death globally. Lifestyle factors and inflammatory bowel conditions such as chronic colitis can heighten the risk of developing the disease. However, research has also linked to the development of colorectal tumours to stress, anxiety and depression. This ‘brain-gut’ connection is particularly less-well understood.

One brain region of interest is the hypothalamus, an almond-sized area which helps to regulate mood and bodily processes using chemical messengers that act on various cells in the body. For instance, Oxt neurons in the hypothalamus produce the hormone oxytocin which regulates emotional and social behaviours. These cells play an important role in modulating anxiety, stress and depression.

To investigate whether they could also influence the growth of colorectal tumours, Pan et al. used various approaches to manipulate the activity of Oxt neurons in mice with colitis-associated cancer. Disrupting the Oxt neurons in these animals increased anxiety-like behaviours and promoted tumour growth. Stimulating these cells, on the other hand, suppressed cancer progression.

Further experiments also showed that treating the mice with celastrol, a plant extract which can act on the hypothalamus, stimulated Oxt neurons and reduced tumour growth. In particular, the compound worked by acting on a nerve structure in the abdomen which relays messages to the gut.

These preliminary findings suggest that the hypothalamus and its Oxt-producing neurons may influence the progression of colorectal cancer in mice by regulating the activity of an abdominal ‘hub’ of the nervous system. Modulating the activity of Oxt-producing neurons could therefore be a potential avenue for treatment.