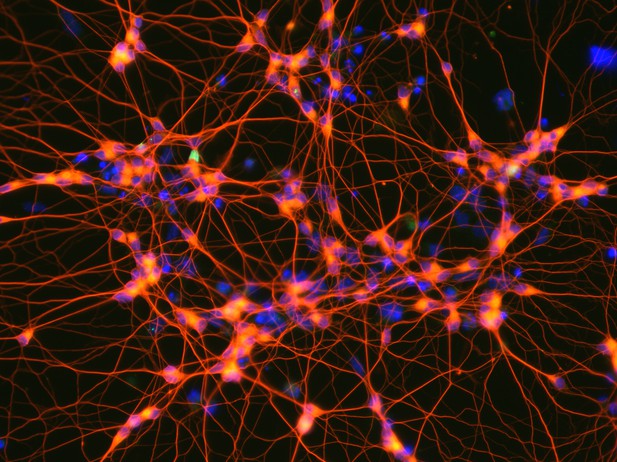

Large web of motor neurons induced by direct programming of mouse embryonic stem cells. Image credit: Penn State (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

We are able to walk, run and move our bodies in other ways thanks to circuits of neurons in the spinal cord that control how and when our muscles contract and relax. Neurons known as premotor neurons receive information from other parts of the central nervous system and control the activities of groups (known as pools) of motor neurons that directly activate individual muscles.

To bend a joint or move our limbs, the movement of different muscles needs to be coordinated. Previous studies have focused on how premotor neurons activate a pool of motor neurons to contract a single muscle, but it remains unclear if and how some of these premotor neurons can co-activate different pools of motor neurons to control more than one muscle at the same time. Here, Ronzano, Lancelin et al. injected mice with modified rabies viruses labelled with different fluorescent markers to build a map of the premotor neurons that connect to motor neurons controlling the leg muscles.

The experiments revealed that many of the individual premotor neurons in the spinal cords of mice connected to different pools of motor neurons. In the upper region of the spinal cord – which is primarily responsible for controlling the front legs – some large premotor neurons activated motor neurons in this region as well as other motor neurons in a lower region of the spinal cord that controls the back legs. This suggests that these large premotor neurons may be important for coordinating muscles contraction within and between limbs.

Many neurological diseases are associated with difficulties in contracting or relaxing muscles. For example, individuals with a condition called dystonia experience disorganized and excessive muscle contractions that prevent them from being able to bend and straighten their joints properly. By helping us to understand how the body coordinates the activities of multiple limbs at the same time, the findings of Ronzano, Lancelin et al. may lead to new lines of research that ultimately improve the quality of life of patients with dystonia and other similar neurological diseases.