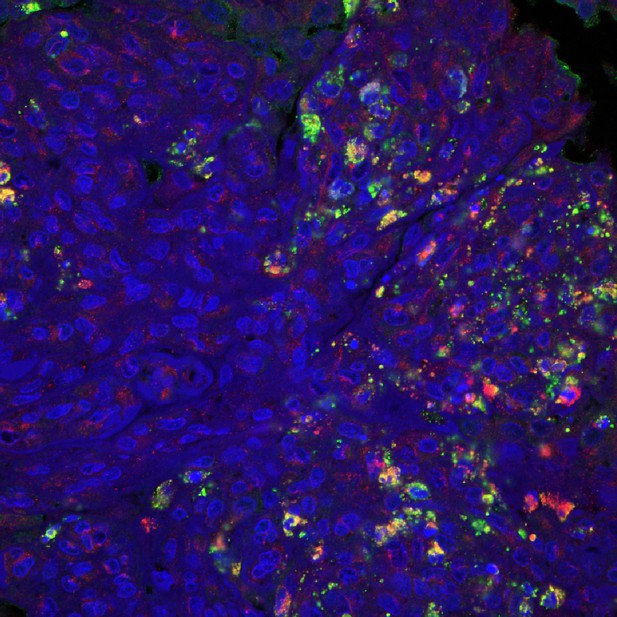

Kidney tissue from a person with lupus, with the DNA shown in blue, AIM2 shown in red and a marker for neutrophils shown in green. Image credit: Brendan Antiochos (CC BY 4.0)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus for short) is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system attacks healthy tissue in organs across the body. The cause is unknown, but people with the illness make antibodies that stick to proteins that are normally found inside the cell nucleus, where DNA is stored. To make these antibodies, the immune system must first ‘see’ these proteins and mistakenly recognise them as a threat. But how does the immune system recognise proteins that are normally hidden inside cells?

During infection, a type of immune cell called a neutrophil releases DNA from its nucleus to form structures called neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs for short. The role of these NETs is to capture and kill pathogens, but they also expose the neutrophil’s DNA and the proteins attached to it to other immune cells. It is therefore possible that other immune cells interacting with NETs during infection may contribute to the development of lupus. Two proteins of interest are AIM2 and IFI16. These proteins form large, shield-like structures around strands of DNA, and previous work has shown that some people with lupus make antibodies against IFI16.

Antiochos et al. wondered whether IFI16 and AIM2 might stick to NETs, exposing themselves to the immune system. Examining the blood of people with lupus revealed that one in three of them made antibodies that could stick to AIM2. Those people were also more likely to have antibodies that could stick to IFI16 and to strands of DNA. Using microscopy, Antiochos et al. also found AIM2 and IFI16 on NETs in the kidneys of some people with lupus. Further investigation showed that the presence of AIM2 and IFI16 prevents NETs from breaking down.

If proteins like AIM2 and IFI16 can stop NETs from breaking down, they could allow the immune system more time to develop antibodies against them. Further investigation could reveal whether this is one of the causes of lupus. A clearer understanding of the antibodies could also boost research into diagnosis and treatment.