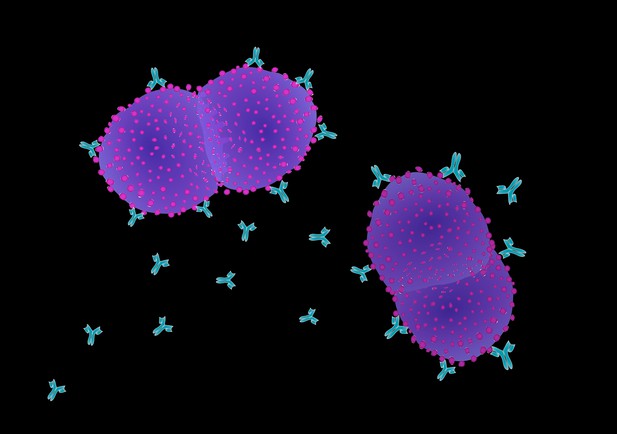

Antibodies produced by a B cell attacking bacteria. Image credit: Saori Fukao (CC BY 4.0)

When the human body faces a potentially harmful microorganism, the immune system responds by finding and destroying the pathogen. This involves the coordination of several different parts of the immune system. B cells are a type of white blood cell that is responsible for producing antibodies: large proteins that bind to specific targets such as pathogens. B cells often need help from other immune cells known as T cells to complete antibody production.

However, T cells are not required for B cells to produce antibodies against some bacteria. For example, when certain pathogenic bacteria coated with a carbohydrate called a capsule – such as pneumococcus, which causes pneumonia, or salmonella – invade our body, B cells recognize a repetitive structure of the capsule using a B-cell antigen receptor. This recognition allows B cells to produce antibodies independently of T cells. It is unclear how B cells produce antibodies in this situation or what proteins are required for this activity.

To understand this process, Fukao et al. used genetically modified mice and their B cells to study how they produce antibodies independently of T cells. They found that a protein called PKCδ is critical for B cells to produce antibodies, especially of an executive type called IgG, in the T-cell-independent response. PKCδ became active when B cells were stimulated with the repetitive antigen present on the surface of bacteria like salmonella or pneumococcus. Mice that lack PKCδ were unable to produce IgG independently of T cells, leading to fatal infections when bacteria reached the tissues and blood.

Understanding the mechanism behind the T cell-independent B cell response could lead to more effective antibody production, potentially paving the way for new vaccines to prevent fatal diseases caused by pathogenic bacteria.