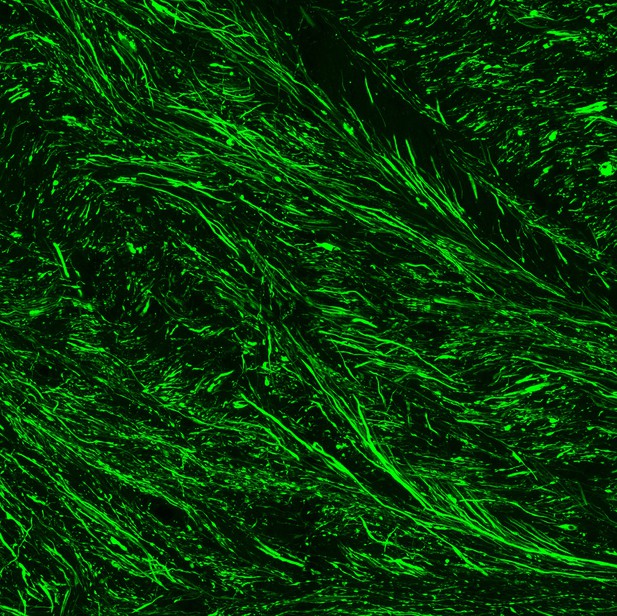

Axons in the brain of a macaque monkey which have been labelled with a green fluorescent protein. Image credit: Yu, Yan et al. (CC BY 4.0)

In the brain is a web of interconnected nerve cells that send messages to one another via spindly projections called axons. These axons join together at junctions called synapses to create circuits of nerve cells which connect neighboring or distant brain regions. Notably, long-range neural connections underpin higher-order cognitive skills (such as planning and emotion regulation) which make humans distinct from our primate relatives. Only by untangling these far-reaching networks can researchers begin to delineate what sets the human brain apart from other species.

Researchers deploy a range of imaging techniques to map neural networks: scanning entire brains using MRI machines, or imaging thin slices of fluorescently labelled brain tissue using powerful microscopes. However, tracing long-range axons at a high resolution is challenging, and has stirred up debate about whether some neural tracts, such as the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, are present in all primates or only humans.

To address these discrepancies, Yan, Yu et al. employed a two-pronged approach to map neural circuits in the brains of macaques. First, two techniques – called viral tracing and two-photon microscopy – were used to create a three-dimensional, fine-grain map showing how the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC), which regulates complex behaviors, connects to the rest of the brain. This revealed prominent axons from the vlPFC projecting via a single synapse to distant brain regions involved in higher-order functions, such as encoding memories and processing emotion. However, there were no direct, monosynaptic connections between the vlPFC and the occipital lobe, the brain’s visual processing center at the back of the head.

Next, Yan, Yu et al. used a specialized MRI scanner to create an atlas of neural circuits connected to the vlPFC, and compared these results to a technique tracing axons stained with a fluorescent dye. In general, there was good agreement between the two methods, except for major differences in the rear-end projections that typically form the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus. This suggests that this long-range neural pathway exists in monkeys, but it connects via multiple synapses instead of a single junction as was previously thought.

The findings of Yan, Yu et al. provide new insights on the far-reaching neural pathways connecting distant parts of the macaque brain. It also suggests that atlases of neural circuits from whole brain scans should be taken with caution and validated using neural tracing experiments.