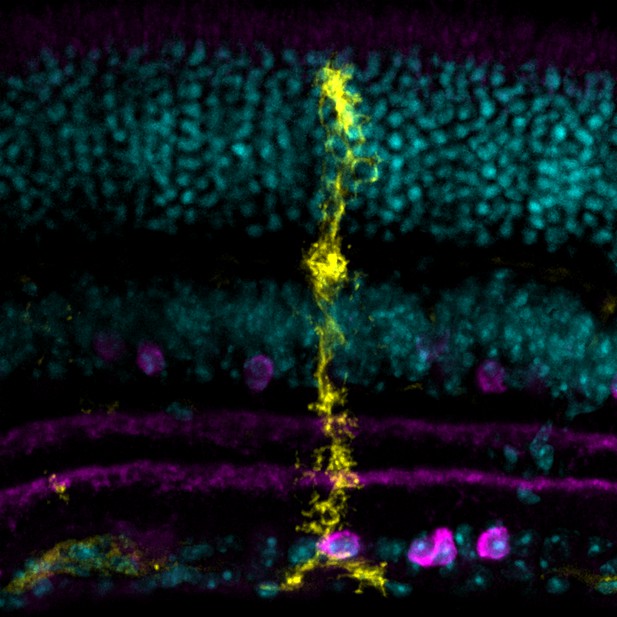

Microscopy image of a Müller glial cell (yellow) and its many specialized membrane processes: some cover cell bodies (cyan), while others extend throughout sublayers rich in synapses, including those that use the messenger acetylcholine to communicate (magenta). Image credit: Tworig et al. (CC BY 4.0) with thanks to Holly Aaron and Feather Ives for microscopy advice and support

When it comes to studying the nervous system, neurons often steal the limelight; yet, they can only work properly thanks to an ensemble cast of cell types whose roles are only just emerging.

For example, ‘glial cells’ – their name derives from the Greek word for glue – were once thought to play only a passive, supporting function in nervous tissues. Now, growing evidence shows that they are, in fact, integrated into neural circuits: their activity is influenced by neurons, and, in turn, they help neurons to function properly.

The role of glial cells is becoming clear in the retina, the thin, light-sensitive layer that lines the back of the eye and relays visual information to the brain. There, beautifully intricate Müller glial cells display fine protrusions (or ‘processes') that intermingle with synapses, the busy space between neurons where chemical messengers are exchanged. These messengers can act on Müller cells, triggering cascades of molecular events that may influence the structure and function of glia. This is of particular interest during development: as Müller cells mature, they are exposed to chemicals released by more fully formed retinal neurons.

Tworig et al. explored how neuronal messengers can influence the way Müller cells grow their processes. To do so, they tracked mouse retinal glial cells ‘live’ during development, showing that they were growing fine, highly dynamic processes in a region rich in synapses just as neurons and glia increased their communication. However, using drugs to disrupt this messaging for a short period did not seem to impact how the processes grew. Extending the blockade over a longer timeframe also did not change the way Müller cells developed, with the cells still acquiring their characteristic elaborate process networks. Taken together, these results suggest that the structural maturation of Müller glial cells is not impacted by neuronal signaling, giving a more refined understanding of how glia form in the retina and potentially in the brain.