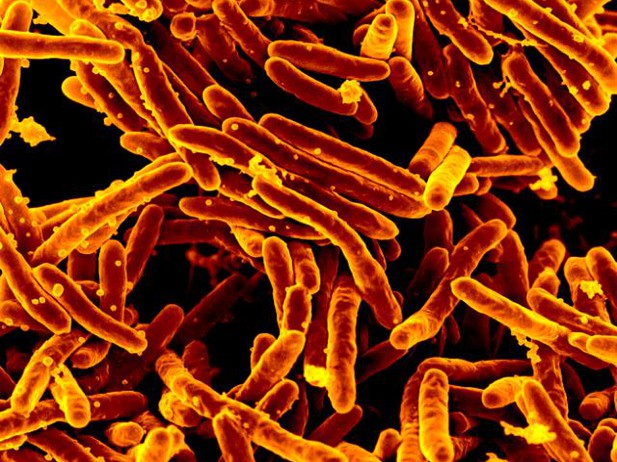

Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Image credit: Public domain

How can you predict which proteins an organism can make? To answer this question, scientists often use computer programs that can scan the genetic information of a species for open reading frames – a type of DNA sequence that codes for a protein. However, very short genes and overlapping genes are often missed through these searches.

Mycobacteria are a group of bacteria that includes the species Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes tuberculosis. Previous work has predicted several thousand open reading frames for M. tuberculosis, but Smith et al. decided to use a different approach to determine whether there could be more. They focused on ribosomes, the cellular structures that assemble a specific protein by reading the instructions provided by the corresponding gene.

Examining the sections of genetic code that ribosomes were processing in M. tuberculosis uncovered hundreds of new open reading frames, most of which carried the instructions to make very short proteins. A closer look suggested that only 90 of these proteins were likely to have a useful role in the life of the bacteria, which could open new doors in tuberculosis research. The rest of the sequences showed no evidence of having evolved a useful job, yet they were still manufactured by the mycobacteria. This pervasive production could play a role in helping the bacteria adapt to quickly changing environments by evolving new, functional proteins.