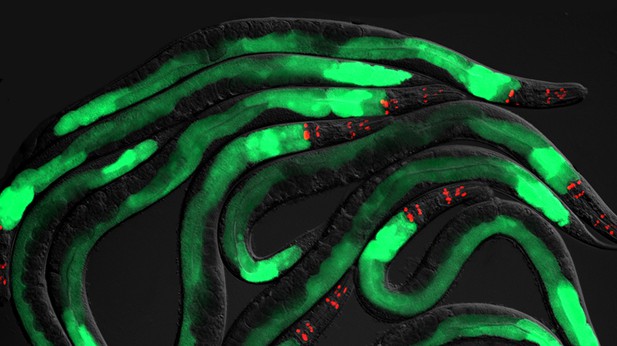

A bacterial infection activates innate immune defences (green) in C. elegans. Image credit: Peterson et al. (CC BY 4.0)

From worms to humans, animals have developed various strategies – including immune defences – to shield themselves from disease-causing microbes. A type of roundworm, called C. elegans, lives in environments rich in microbes, so it needs effective immune defences to protect itself. The roundworms share a key regulatory pathway with mammals that helps to control their immune responses. This so-called p38 pathway relies on proteins that interact with each other to activate protective immune defences.

Proteins contain different regions or domains that can give them a certain function. For example, proteins with a region called TIR play important roles in immune defences in both animals and plants. One such protein, called SARM1, is unique among animal and plant proteins in that it is an enzyme, which cleaves an important metabolite in the cell. In C. elegans, the SARM1 homolog, TIR-1, controls the p38 pathway during infection, but how TIR-1 activates it is unclear.

To find out more, Peterson, Icso et al. modified C. elegans to generate a fluorescent form of TIR-1 and infected the worms with bacteria. Imaging techniques revealed that infection caused TIR-1 in gut cells to cluster into organized structures, which increases the enzymatic activity of the protein to activate the p38 immune pathway. Moreover, stress situations, such as cholesterol nutrient withdrawal, activated the p38 pathway in the same way. This adaptive stress response allows the animal to defend itself against pathogen threats during times, when they are most susceptible to infections.

Cells in the gut provide a primary line of defence against infectious bacteria and are important for maintaining a healthy gut immune system. When the mechanisms for pathogen sensing and immune maintenance are disrupted, it can lead to inflammation and higher risk of infection. Peterson, Icso et al. show how a key regulator of gut immunity, TIR-1, provides protection in C. elegans, which may suggest that SARM1 could have a similar role in mammals.