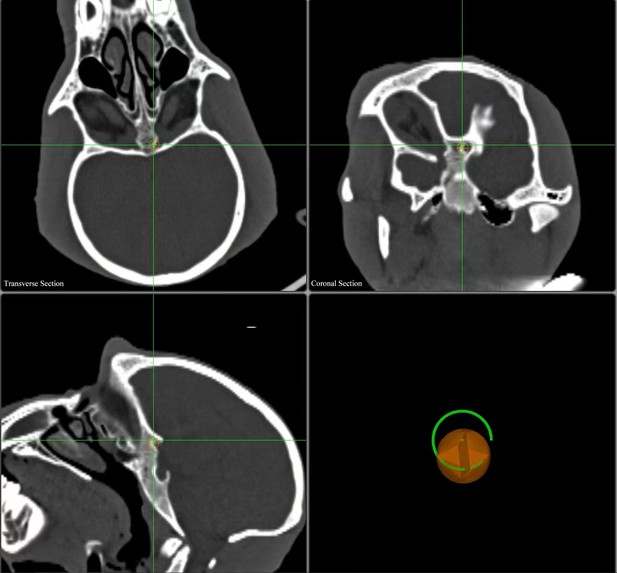

Stills of the surgical navigation system developed by Zhang et al. Image credit: Yikui Zhang and Lujie Zhang (CC BY 4.0)

Hypothermic therapy is a radical type of treatment that involves cooling a person’s core body temperature several degrees below normal to protect against brain damage. Lowering body temperature slows blood flow, which reduces inflammation, and eases metabolic demands, similar to hibernation. It can also reduce lasting damage to the brain and aid recovery when used to treat people who have gone into cardiac arrest, where their heart suddenly stops beating.

Recently, there has been renewed interest in using hypothermic therapy to treat people who have sustained traumatic brain injuries, which can cause brain swelling, and other nerve injuries. However, its use remains controversial because clinical trials have failed to show that inducing mild hypothermia provides any benefit for people with severe nerve injuries. This might be because cooling cells to near-freezing temperatures can damage their internal structural supports, called microtubules, thwarting any therapeutic benefit.

Traumatic optical neuropathy is a type of injury in which the optic nerve – the nerve that connects the eyes to the brain – is damaged or severed, causing vision loss. There is currently no clinically proven treatment for this condition, nor is there a system that can test local treatments in large animals as a prior test to using the treatment in the clinic. Therefore, Zhang et al. wanted to establish such a animal model and test whether local hypothermic therapy could help protect the optic nerve.

Zhang et al. used a surgical tool guided by an endoscope (a thin plastic tube with a light and camera attached to it) to injure the optic nerves of goats, and then deliver hypothermic therapy. To cool the surgically-injured nerves to a chilly 4C, Zhang et al. applied a deep-cooling agent, using a second reagent (a cocktail of protease inhibitors) to protect the cells’ microtubules from cold-induced damage, an insight gained from a previous study of hibernating animals. This was critical, as the hypothermic therapy was only effective when the secondary protective agent was applied. The combination therapy developed by Zhang et al. relieved some aspects of nerve degeneration at the injury site and activated an anti-inflammatory response in cells, but did not restore vision.

To simplify surgical techniques, Zhang et al. also developed a computer program which generates virtual surgical paths for up-the-nose endoscopic procedures based on brain scans of an animal’s skull. This program was successfully applied in a range of large animals, including goats and macaque monkeys.

Zhang et al.’s work establishes a method to study treatments for traumatic optical neuropathy using large animals, including hypothermic therapy. The methods developed could also be useful to study other optic nerve disorders, such as optic neuritis or ischemic optic neuropathy.