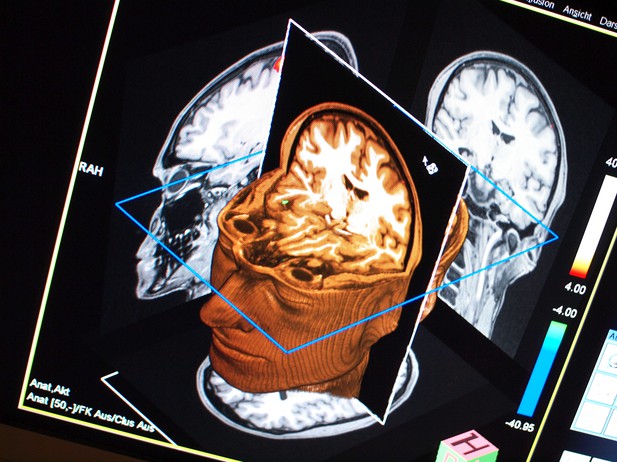

Imaging the human brain. Image credit: Martin Hieslmair (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

When it comes to making decisions, like choosing a restaurant or political candidate, most of us rely on limited information that is not accurate enough to find the best option. Considering others’ decisions and opinions can help us make smarter choices, a phenomenon called “collective intelligence”.

Collective intelligence relies on individuals making unbiased decisions. If individuals are biased toward making poor choices over better ones, copying the group’s behavior may exaggerate biases. Humans are persistently biased. To avoid repeated failure, humans tend to avoid risky behavior. Instead, they often choose safer alternatives even when there might be a greater long-term benefit to risk-taking. This may hamper collective intelligence.

Toyokawa and Gaissmaier show that learning from others helps humans make better decisions even when most people are biased toward risk aversion. The experiments first used computer modeling to assess the effect of individual bias on collective intelligence. Then, Toyokawa and Gaissmaier conducted an online investigation in which 185 people performed a task that involved choosing a safer or risker alternative, and 400 people completed the same task in groups of 2 to 8. The online experiment showed that participating in a group changed the learning dynamics to make information sampling less biased over time. This mitigated people’s tendency to be risk-averse when risk-taking is beneficial.

The model and experiments help explain why humans have evolved to learn through social interactions. Social learning and the tendency of humans to conform to the group’s behavior mitigates individual risk aversion. Studies of the effect of bias on individual decision-making in other circumstances are needed. For example, would the same finding hold in the context of social media, which allows individuals to share unprecedented amounts of sometimes incorrect information?