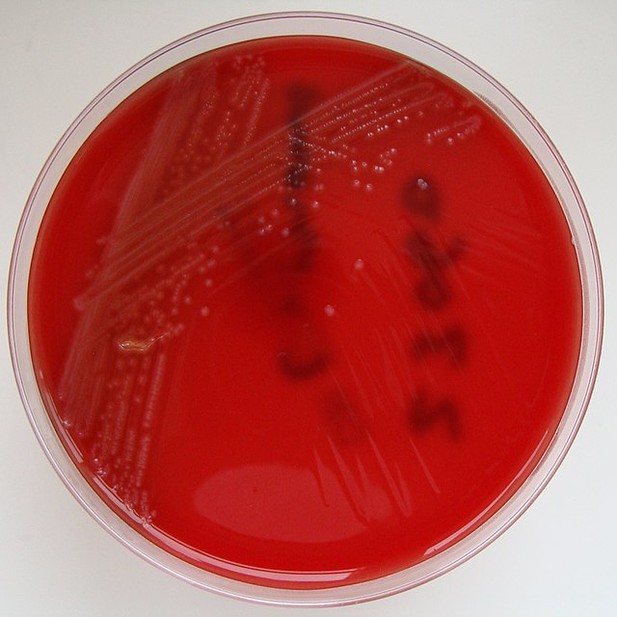

Listeria monocytogenes. Image credit: Nathan Reading (CC BY 2.0)

Cellular respiration is one of the main ways organisms make energy. It works by linking the oxidation of an electron donor (like sugar) to the reduction of an electron acceptor (like oxygen). Electrons pass between the two molecules along what is known as an ‘electron transport chain’. This process generates a force that powers the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a molecule that cells use to store energy.

Respiration is a common way for cells to replenish their energy stores, but it is not the only way. A simpler process that does not require a separate electron acceptor or an electron transport chain is called fermentation. Many bacteria have the capacity to perform both respiration and fermentation and do so in a context-dependent manner.

Research has shown that respiration can contribute to bacterial diseases, like tuberculosis and listeriosis (a disease caused by the foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes). Indeed, some antibiotics even target bacterial respiration. Despite being often discussed in the context of generating ATP, respiration is also important for many other cellular processes, including maintaining the balance of reduced and oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) cofactors. Because of these multiple functions, the exact role respiration plays in disease is unknown.

To find out more, Rivera-Lugo, Deng et al. developed strains of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes that lacked some of the genes used in respiration. The resulting bacteria were still able to produce energy, but they became much worse at infecting mammalian cells. The use of a genetic tool that restored the balance of reduced and oxidized NAD cofactors revived the ability of respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes to infect mammalian cells, indicating that this balance is what the bacterium requires to infect.

Research into respiration tends to focus on its role in generating ATP. But these results show that for some bacteria, this might not be the most important part of the process. Understanding the other roles of respiration could change the way that researchers develop antibacterial drugs in the future. This in turn could help with the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.