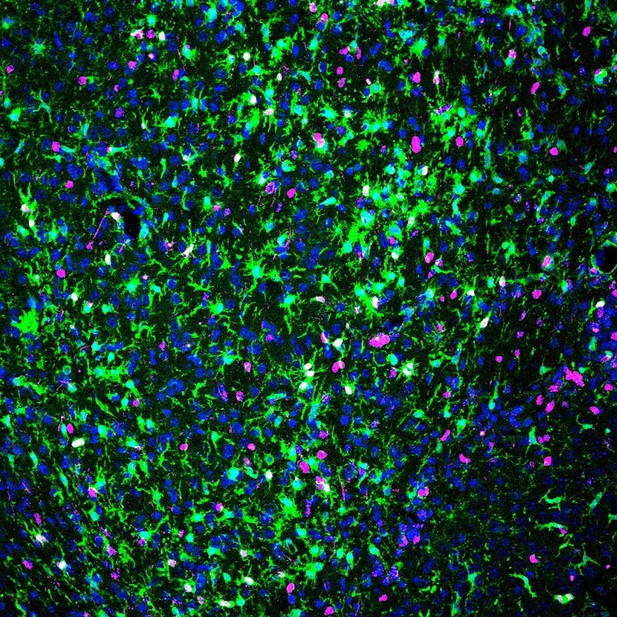

Image showing different cells (blue) in the brain of a mouse after hypoxic-ischemic injury, including immune cells (green) which are dividing (shown in pink) and becoming activated. Image credit: Lauritz Kennedy (CC BY 4.0)

Hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury is the most common cause of disability in newborn babies. This happens when the blood supply to the brain is temporarily blocked during birth and cells do not receive the oxygen and nutrients they need to survive. Cooling the babies down after the hypoxic-ischemic attack (via a technique called hypothermic treatment) can to some extent reduce the damage caused by the injury. However, doctors still need new drugs that can protect the brain and improve its recovery after the injury has occurred.

Research in mice suggests that a chemical called lactate might help the brain to recover. Lactate is produced by muscles during hard exercise to provide energy to cells when oxygen levels are low. Recent studies have shown that it can also act as a signalling molecule that binds to a receptor called HCAR1 (short for hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor) on the surface of cells. However, it is poorly understood what role HCAR1 plays in the brain and whether it helps the brain recover from a hypoxic-ischaemic injury.

To investigate, Kennedy et al. compared newborn mice with and without the gene that codes for HCAR1 that had undergone a hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury. While HCAR1 did not protect the mice from the disease, it did help their brains to heal. Mice with the gene for HCAR1 partly recovered some of their damaged brain tissue six weeks after the injury. Their cells switched on thousands of genes involved in the immune system and cell cycle, resulting in new brain cells being formed that could repopulate the injured areas. In contrast, the brain tissue of mice lacking HCAR1 barely produced any new cells.

These findings suggest that HCAR1 may help with brain recovery after hypoxia-ischemia in newborn mice. This could lead to the development of drugs that might reduce or repair brain damage in newborn babies. However, further studies are needed to investigate whether HCAR1 has the same effect in humans.