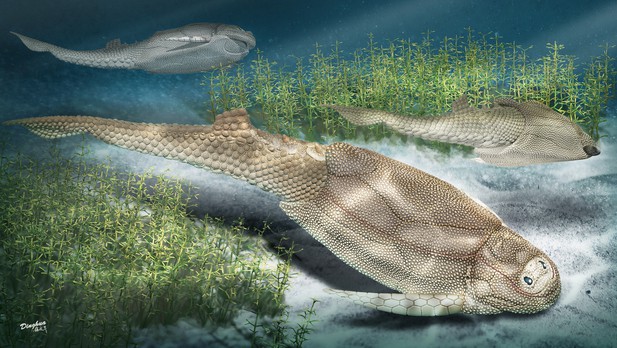

Graphical representation of the extinct species Parayunnanolepis xitunensis. Image credit: Dinghua Yang (CC BY 4.0)

Many vertebrates have an outer skeleton covering their body. Some, like crocodiles, have large bony plates of armor, while others, like fish, have small slippery scales. The type, shape, and arrangement of these structures can tell scientists a lot about how different species evolved.

Most modern fish are completely covered in scales, but this has not always been the case. Over 400 millions of years ago in the Earth’s oceans lived a major group of armored fish called antiarch placoderms which had a combination of bony plates, scales and naked skin. These ancient fish are particularly interesting to scientists because they were one of the first jawed vertebrates to evolve. However, much of what is known about this group has come from isolated materials, which has made it difficult to study the organization and shape of their scales.

To overcome this, Wang and Zhu used a specialized x-ray imaging procedure to create a three-dimensional model of one of the best-preserved antiarch placoderm species, Parayunnanolepis xitunensis. The model showed that the fish had thirteen types of scales, found in nine distinct regions on its body.

To better understand the structure of these scales, Wang and Zhu looked at the fossils of other extinct jawed fish which where were found in the region where P. xitunensis once lived. The scales of these ancient fish were very different from their bony plates, and from the scales of modern fish.

Understanding the skin armor of ancient fish could help to explain how the scales of modern vertebrates evolved. The next step is to look in more detail at the scales of other placoderms to see how they changed over time.