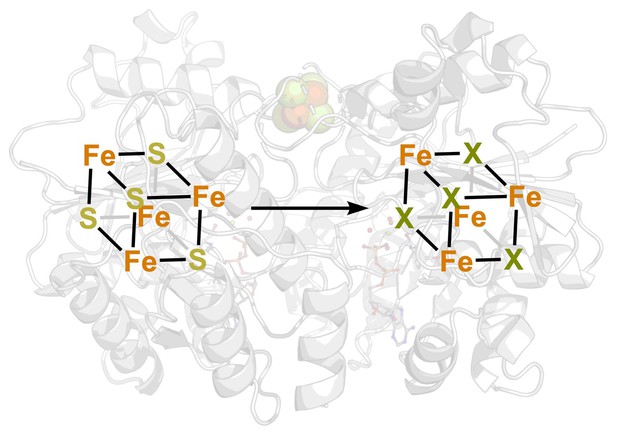

The iron sulfur cluster of the Fe protein (structure in the background) is shown as a cube with iron ions shown in orange (Fe) and sulfur ions shown in yellow (S). When the cluster reacts with selenocyanate, it can exchange some or all of its sulfur ions for selenium ions (on the right, mixture of sulfur and selenium ions shown as green Xs). Image credit: Trixia M. Buscagan (CC BY 4.0)

Many of the molecules that form the building blocks of life contain nitrogen. This element makes up most of the gas in the atmosphere, but in this form, it does not easily react, and most organisms cannot incorporate atmospheric nitrogen into biological molecules. To get around this problem, some species of bacteria produce an enzyme complex called nitrogenase that can transform nitrogen from the air into ammonia. This process is called nitrogen fixation, and it converts nitrogen into a form that can be used to sustain life.

The nitrogenase complex is made up of two proteins: the MoFe protein, which contains the active site that binds nitrogen, turning it into ammonia; and the Fe protein, which drives the reaction. Besides the nitrogen fixation reaction, the Fe protein is involved in other biological processes, but it was not thought to bind directly to nitrogen, or to any of the other small molecules that the nitrogenase complex acts on. The Fe protein contains a cluster of iron and sulfur ions that is required to drive the nitrogen fixation reaction, but the role of this cluster in the other reactions performed by the Fe protein remains unclear.

To better understand the role of this iron sulfur cluster, Buscagan, Kaiser and Rees used X-ray crystallography, a technique that can determine the structure of molecules. This approach revealed for the first time that when nitrogenase reacts with a small molecule called selenocyanate, the selenium in this molecule can replace the sulfur ions of the iron sulfur cluster in the Fe protein. Buscagan, Kaiser and Rees also demonstrated that the Fe protein could still incorporate selenium ions in the absence of the MoFe protein, which has traditionally been thought to provide the site essential for transforming small molecules.

These results indicate that the iron sulfur cluster in the Fe protein may bind directly to small molecules that react with nitrogenase. In the future, these findings could lead to the development of new molecules that artificially produce ammonia from nitrogen, an important process for fertilizer manufacturing. In addition, the iron sulfur cluster found in the Fe protein is also present in many other proteins, so Buscagan, Kaiser and Rees’ experiments may shed light on the factors that control other biological reactions.