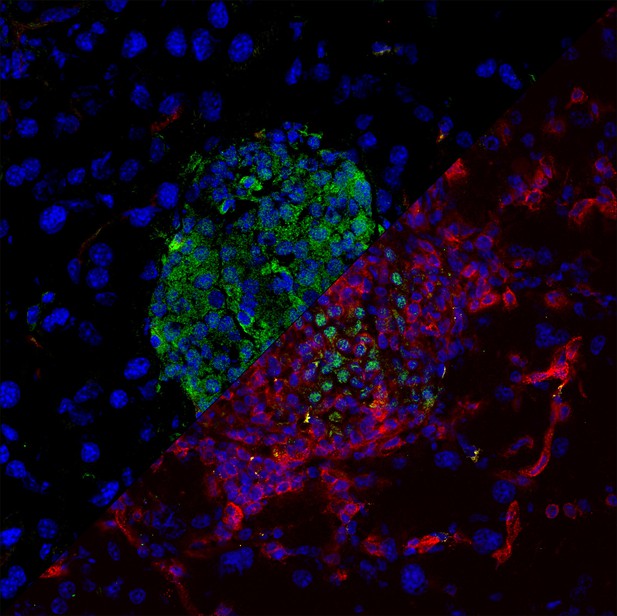

Group of pancreatic cells (nuclei stained in blue) responsible for producing insulin (shown in green) from a healthy mouse (upper left), and a mouse with autoimmune diabetes which has T cells (shown in red and yellow) infiltrating its pancreatic tissue (bottom right). Image credit: Oksana Tsyklauri (CC BY 4.0)

As well as protecting us from invading pathogens, like bacteria or viruses, our immune system can also identify dangerous cells of our own that may cause the body harm, such as cancer cells. Once detected, a population of immune cells called cytotoxic T cells launch into action to kill the potentially harmful cell. However, sometimes the immune system makes mistakes and attacks healthy cells which it misidentifies as being dangerous, leading to autoimmune diseases.

Special immune cells called T regulatory lymphocytes, or ‘Tregs’, can suppress the activity of cytotoxic T cells, preventing them from hurting the body’s own cells. While this can have a positive impact and reduce the effects of autoimmunity, Tregs can also make the immune system less responsive to cancer cells and allow tumors to grow. But how Tregs alter the behavior of cytotoxic T cells during autoimmune diseases and cancer is poorly understood. While multiple mechanisms have been proposed, none of these have been tested in living animal models of these diseases.

To address this, Tsyklauri et al. studied Tregs in laboratory mice which had been modified to have autoimmune diabetes, which is when the body attacks the cells responsible for producing insulin. The experiments revealed that Tregs take up a critical signaling molecule called IL-2 which cytotoxic T cells need to survive and multiply. As a result, there is less IL-2 molecules available in the environment, inhibiting the cytotoxic T cells’ activity. Furthermore, if Tregs are absent and there is an excess of IL-2, this causes cytotoxic T cells to transition into a previously unknown subset of T cells with superior killing abilities.

Tsyklauri et al. were able to replicate these findings in two different groups of laboratory mice which had been modified to have cancer. This suggests that Tregs suppress the immune response to cancer cells and prevent autoimmunity using the same mechanism. In the future, this work could help researchers to develop therapies that alter the behavior of cytotoxic T cells and/or Tregs to either counteract autoimmune diseases, or help the body fight off cancer.