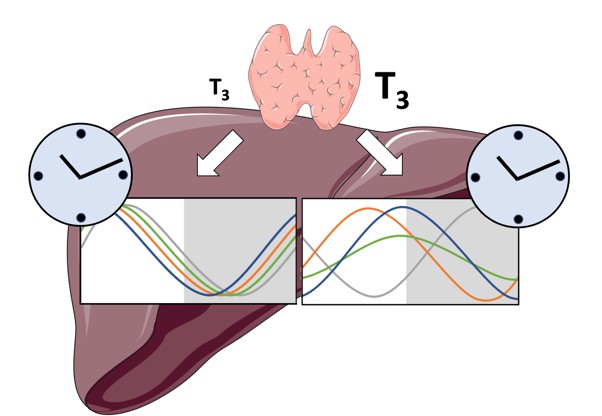

Normal levels of thyroid hormones maintain the daily rhythms of gene activity in the liver (left), while high levels disrupt this rhythmicity (right). Image credit: de Assis, Harder et al. (CC BY 3.0)

Many environmental conditions, including light and temperature, vary with a daily rhythm that affects how animals interact with their surroundings. Indeed, most species have developed so-called circadian clocks: internal molecular timers that cycle approximately every 24 hours and regulate many bodily functions, including digestion, energy metabolism and sleep.

The energy metabolism of the liver – the chemical reactions that occur in the organ to produce energy from nutrients – is controlled both by the circadian clock system, and by the hormones produced by a gland in the neck called the thyroid. However, the interaction between these two regulators is poorly understood. To address this question, de Assis, Harder et al. elevated the levels of thyroid hormones in mice by adding these hormones to their drinking water.

Studying these mice showed that, although thyroid hormone levels were good indicators of how much energy mice burn in a day, they do not reflect daily fluctuations in metabolic rate faithfully. Additionally, de Assis, Harder et al. showed that elevating T3, the active form of thyroid hormone, led to a rewiring of the daily rhythms at which genes were turned on and off in the liver, affecting the daily timing of processes including fat and cholesterol metabolism. This occurred without changing the circadian clock of the liver directly.

De Assis, Harder et al.’s results indicate that time-of-day critically affects the action of thyroid hormones in the liver. This suggests that patients with hypothyroidism, who produce low levels of thyroid hormones, may benefit from considering time-of-day as a factor in disease diagnosis, therapy and, potentially, prevention. Further data on the rhythmic regulation of thyroid action in humans, including in patients with hypothyroidism, are needed to further develop this approach.