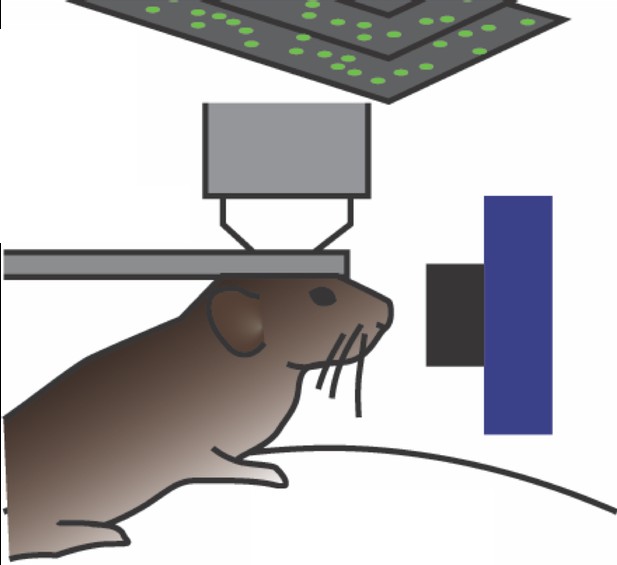

Experimental setup used by Jones et al. Image credit: Woodrow Shew (CC BY 4.0)

As we go about our days, how often do we fidget, compared to how frequently we make larger movements, like walking down the hall? And how rare is a trek across town compared to that same walk down the hall? Animals tend to follow a mathematical law that relates the size of our movements to how often we do them.

This law posits that small-to-medium movements and large-to-huge movements are related in the same way, that is, the law is ‘scale-free’, it holds the same for different scales of movement. Surprisingly, measurements of brain activity also follow this scale-free law: the level of activation of a group of neurons relates to how often they are activated in the same way for different levels of activation.

Although body movements and brain activity behave in a mathematically similar way, these two facts had not previously been linked. Jones et al. studied body movements and brain activity in mice, and found that scale-free body movements were linked to scale-free brain activity, but only in certain subsets of neurons. This observation had been hidden because other subsets of neurons compete with scale-free neurons. When the scale-free neurons turn on, the competing groups turn off. When averaged together, these fluctuations cancel out.

The findings of Jones et al. provide a new understanding of how brain and body dynamics are orchestrated in healthy organisms. In particular, their results suggest that the complex, multi-scale nature of behavior and body movements may emerge from brain activity operating at a critical tipping point between order and disorder, at the edge of chaos.