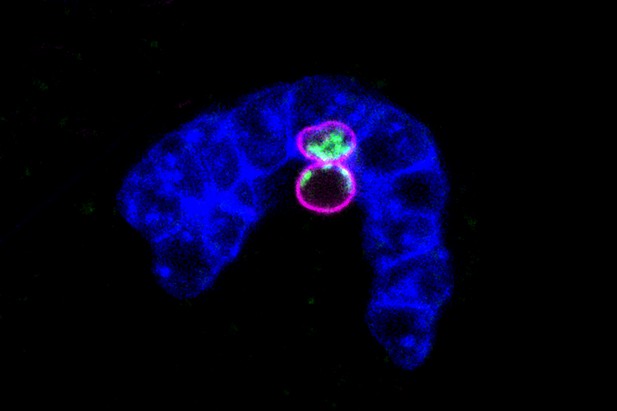

Egg precursor cells of C. elegans (magenta) with mitochondria (green embedded in adjacent endodermal cells (blue). Image credit: Schwartz et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Mitochondria are the powerhouses of every cell in our bodies. These tiny structures convert energy from the food we eat into a form that cells are able to use. As well as being a separate organ-like structure within our cells, mitochondria even have their own DNA. Mitochondrial DNA contains genes for a small number of special enzymes that allow it to extract energy from food. In contrast, the rest of our cells’ DNA is stored in another structure called the nucleus.

Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA are also inherited differently. We inherit nuclear DNA from both our mother and father, but mitochondrial DNA is only passed down from our mothers. During reproduction, maternal DNA (including mitochondrial DNA) comes from the egg cell, which combines with sperm to produce offspring.

Defects, or mutations, in mitochondrial genes often lead to mitochondrial diseases. These have a severe impact on health, especially during the very first stages of life. The lineage of precursor cells that gives rise to egg cells is thought to protect itself from mitochondrial mutations, but how it does this is still unclear. Schwartz et al. therefore set out to determine what molecular mechanisms preserve the integrity of mitochondrial DNA from one generation to the next.

To address this question, C. elegans roundworms were used, as they are easy to manipulate genetically, and since they are small and transparent, their cells – as well as their mitochondria – are also easily viewed under a microscope. Tracking mitochondria in the worms’ egg precursor cells (also called primordial germ cells, or PGCs) revealed that PGCs actively removed excess mitochondria. The PGCs did this either by internally breaking down mitochondria themselves, or by moving them into protruding lobe-like structures which surrounding cells then engulfed and ‘digested’.

Further genetic studies revealed that the PGCs also directly regulated the quality of mitochondrial DNA via a mechanism dependent on the protein PINK1. In worms lacking PINK1, mutant mitochondrial DNA remained in the PGCs at high levels, whereas normal worms successfully reduced the mutant DNA. Thus, the PGCs used parallel mechanisms to control both the quantity and quality of mitochondria passed to the next generation.

These results contribute to our understanding of how organisms safeguard their offspring from inheriting mutant mitochondrial DNA. In the future, Schwartz et al. hope that this knowledge will help us treat inherited mitochondrial diseases in humans.