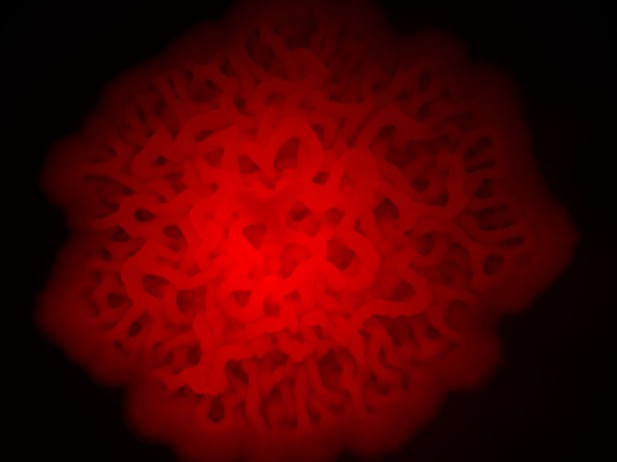

Fluorescent image of a biofilm colony of one of the yeast strains. Image credit: Ekdahl et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Yeast are microscopic fungi that are found on many plants, in the soil and in other environments around the world. But, when given the chance, some yeasts are also good at infecting human and other animals and causing disease.

It has been proposed that some opportunistic microbes may have dual-use traits that evolved for one purpose in their natural environment but also incidentally allow them to infect animals. For example, a toxin that helps the opportunistic microbe compete against neighboring microbes may also weaken an animal. Or the ability of many individual microbe cells to clump together into structures known as biofilms on solid surfaces, or floating mats called flors on liquids, helps them to survive in harsh environments, whether in the soil or in the body of an animal.

To investigate this possibility, Ekdahl, Salcedo et al. examined whether artificially selecting yeast with a specific trait – the ability to stick to plastic beads – in the absence of any host animals would inadvertently also select for yeast that were good at causing disease. This trait was selected because it has not been previously linked to opportunistic yeast infections.

The team grew the yeast for 400 generations in tubes that each contained a plastic bead. At every generation, only yeast that stuck to the plastic bead were transferred to a fresh tube to grow the next generation. The experiments found that, not only did the ability of the yeast to stick to the plastic increase over time, but the yeast also evolved the ability to form biofilms and flors. Furthermore, the sticky yeast killed an insect host known as wax moth larvae more quickly than non-sticky yeast.

Together, these findings demonstrate that when microbes evolve in an environment that is devoid of any host animals, selection can inadvertently favor dual-use traits that also help the yeast to infect animals. Opportunistic yeast infections are of increasing concern in human patients, particularly those with weakened immune systems. Understanding which yeast traits are dual-use will help guide future efforts in combatting yeast and other opportunistic microbes.