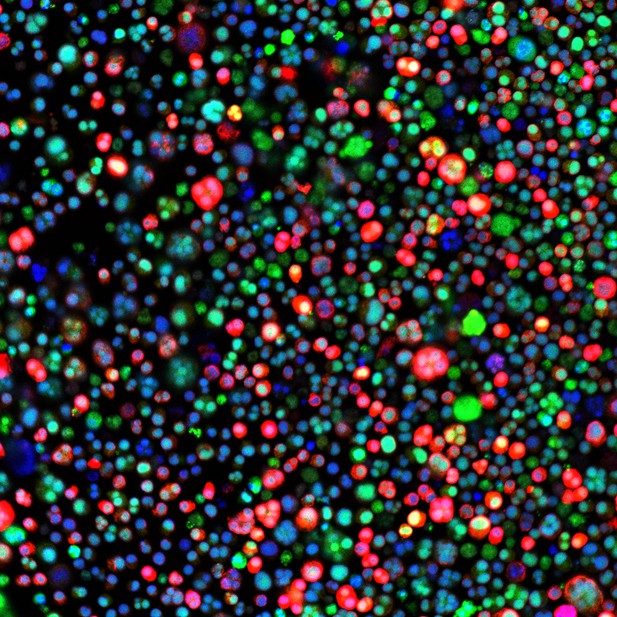

Microscopy image of myeloma cells (green with blue cell nuclei) that express the protein FABP5 (red). Image credit: Farrell et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Multiple myeloma is a type of blood cancer for which only a few treatments are available. Currently, only about half the patients with multiple myeloma survive for five years after diagnosis. Because obesity is a risk factor for multiple myeloma, researchers have been studying how fat cells or fatty acids affect multiple myeloma tumor cells to identify new treatment targets.

Fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs) are one promising target. The FABPs shuttle fatty acids and help cells communicate. Previous studies linked FABPs to some types of cancer, including another blood cancer called leukemia, and cancers of the prostate and breast. A recent study showed that patients with multiple myeloma, who have high levels of FABP5 in their tumors, have worse outcomes than patients with lower levels. But, so far, no one has studied the effects of inhibiting FABPs in multiple myeloma tumor cells or animals with multiple myeloma.

Farrell et al. show that blocking or eliminating FABPs kills myeloma tumor cells and slows their growth in a dish (in vitro) and in some laboratory mice. In the experiments, the researchers treated myeloma cells with drugs that inhibit FABPs or genetically engineered myeloma cells to lack FABPs. They also show that blocking FABPs reduces the activity of a protein called MYC, which promotes tumor cell survival in many types of cancer. It also changed the metabolism of the tumor cell. Finally, the team examined data collected from several sets of patients with multiple myeloma and found that patients with high FABP levels have more aggressive cancer.

The experiments lay the groundwork for more studies to determine if drugs or other therapies targeting FABPs could treat multiple myeloma. More research is needed to determine why inhibiting FABPs worked in some mice with multiple myeloma but not others, and whether FABP inhibitors might work better if combined with other cancer therapies. There were no signs that the drugs were toxic in mice, but more studies must prove they are safe and effective before testing the drugs in humans with multiple myeloma. Designing better or more potent FABP-blocking drugs may also lead to better animal study results.