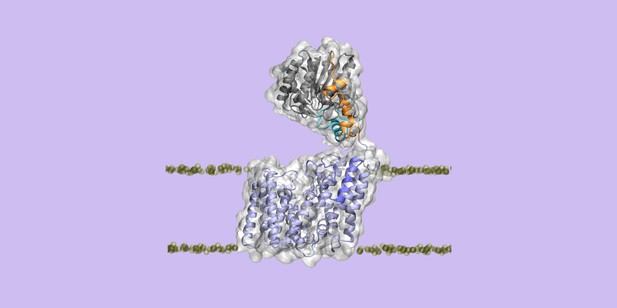

The membrane protein OafB is formed of two domains. One is anchored in the membrane (purple helices) and contains newly described structures which allow acyl groups to cross the membrane; this forms a working partnership with the second domain (orange, green and dark grey elements) to modify a surface structure. Image credit: Kahlan Newman (CC BY 4.0)

The fatty membrane that surrounds cells is an essential feature of all living things. It is a selective barrier, only allowing certain substances to enter and exit the cell, and it contains the proteins and carbohydrates that the cell uses to interact with its environment. In bacteria, the carbohydrates on the outer side of the membrane can become ‘tagged’ or modified with small chemical entities which often prove useful for the cell. Acyl groups, for example, allow disease-causing bacteria to evade the immune system and contribute to infections persisting in the body.

As a rule, activated acyl groups are only found inside the cell, so they need to move across the membrane before they can be attached onto the carbohydrates at the surface. This transfer is performed by a group of proteins that sit within the membrane called the acyltransferase-3 (AT3) family. The structure of these proteins and the mechanism by which they facilitate membrane crossing have remained unclear.

Newman, Tindall et al. combined computational and structural modelling techniques with existing experimental data to establish how this family of proteins moves acyl groups across the membrane. They focused on OafB, an AT3 protein from the foodborne bacterial pathogen Salmonella typhimurium. The experimental data used by the team included information about which parts of OafB are necessary for this protein to acylate carbohydrates molecules.

In their experiments, Newman, Tindall et al. studied how different parts of OafB move, how they interact with the molecules that carry an acyl group to the membrane, and how the acyl group is then transferred to the carbohydrate acceptor. Their results suggest that AT3 family proteins have a central pore or hole, plugged by a loop. This loop moves and therefore ‘unplug’ the pore, resulting in the emergence of a channel across the membrane. This channel can accommodate the acyl-donating molecule, presenting the acyl group to the outer surface of the membrane where it can be transferred to the acceptor carbohydrate.

The AT3 family of proteins participates in many cellular processes involving the membrane, and a range of bacterial pathogens rely on these proteins to successfully infect human hosts. The results of Newman Tindall et al. could therefore be used across the biological sciences to provide more detailed understanding of the membrane, and to inform the design of drugs to fight bacterial diseases.