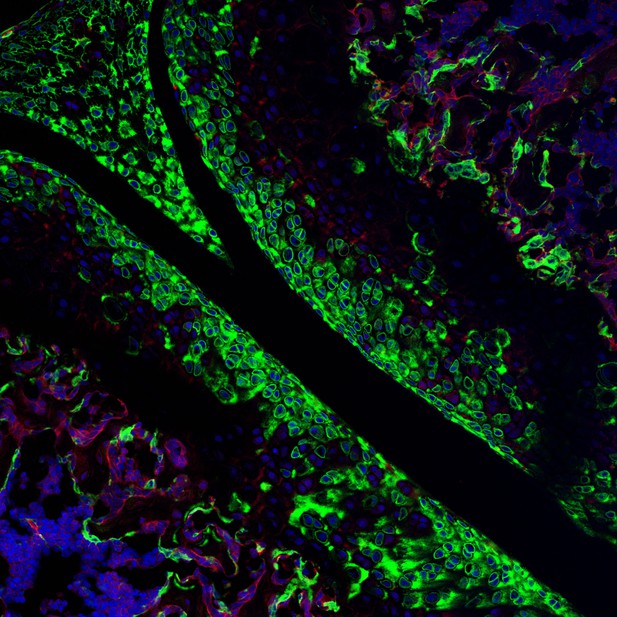

Articular cartilage cells (green) in the knee joint of a mouse that came from progenitor cells containing the protein NFATc1. Image credit: Xianpeng Ge (CC BY 4.0)

Within the body are about 300 joints connecting bones together. Many factors – including trauma, inflammation, aging, and genetic changes – can affect the cushion tissue covering the end of the bones in these joints known as articular cartilage. This can lead to diseases such as osteoarthritis which cause chronic pain, and in some cases disability.

To treat such conditions, it is essential to know how cells in the articular cartilage are formed during development. In the embryo, most cells come from groups of progenitor cells that are programmed to produce specific types of tissue. But which progenitor cells are responsible for producing the main cells in articular cartilage, chondrocytes, and the mechanisms that govern this transformation are poorly understood.

In 2016, a group of researchers found that the gene for the protein NFATc1, which is important for building bone, is also expressed in a group of progenitor cells at the site where ligaments insert into bone in mice. Inactivation of NFATc1 in these progenitor cells has also been shown to cause abnormal cartilage to form, a condition termed osteochondromas. Building on this work, Zhang, Wang et al. – including some of the researchers involved in the 2016 study – set out to find whether NFATc1 is also involved in the normal development of articular chondrocytes.

To investigate, the team used genetically modified mice in which any cells with NFATc1 also had a green fluorescent protein, and tracked these cells and their progeny over the course of joint development. This led them to discover a group of NFATc1-containing progenitor cells that gave rise to almost all articular chondrocytes in the knee joint.

Further experiments revealed that when NFATc1 was removed, this made the progenitors become articular chondrocytes very quickly. In contrast, when the cells had excess amounts of the protein, the formation of articular chondrocytes was significantly reduced. This suggests that the level of NFATc1 governs when progenitors develop into articular chondrocytes.

These findings have provided a way to track the progenitors of articular chondrocytes throughout development and study how articular cartilage is formed. In the future, this work could help researchers develop treatment strategies for osteoarthritis and other cartilage-based diseases. However, before this can happen, further work is needed to confirm that the effects observed in this study also relate to humans.