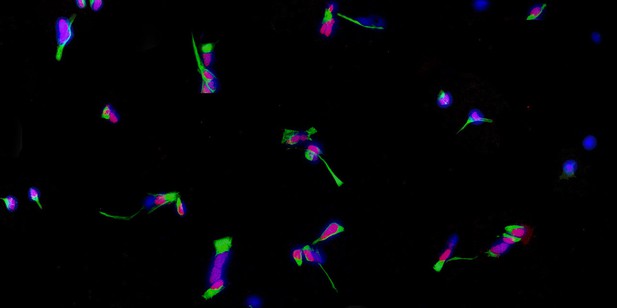

Neural precursor cells derived from an individual with autism that are stained to show the proteins Nestin (green) and PAX6 (red) as well as double stranded DNA (blue). Image credit: Prem et al. (CC BY 4.0).

Although the clinical presentation of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can vary widely, the core features are repetitive behaviors and difficulties with social interactions and communication. In most cases, the cause of autism is unknown. However, in some cases, such as a form of ASD known as 16p11.2 deletion syndrome, specific genetic changes are responsible.

Despite this variability in possible causes and clinical manifestations, the similarity of the core behavioral symptoms across different forms of the disorder indicates that there could be a shared biological mechanism. Furthermore, genetic studies suggest that abnormalities in early fetal brain development could be a crucial underlying cause of ASD. In order to form the complex structure of the brain, fetal brain cells must migrate and start growing extensions that ultimately become key structures of neurons.

To test for shared biological mechanisms, Prem et al. reprogrammed blood cells from people with either 16p11.2 deletion syndrome or ASD with an unknown cause to become fetal-like brain cells. Experiments showed that both migration of the cells and their growth of extensions were similarly disrupted in the cells derived from both groups of individuals with autism.

These crucial developmental changes were driven by alterations to an important signaling molecule in a pathway involved in brain function, known as the mTOR pathway. However, in some cells the pathway was overactive, whereas in others it was underactive. To probe the potential of the mTOR pathway as a therapeutic target, Prem et al. tested drugs that manipulate the pathway, finding that they could successfully reverse the defects in cells derived from people with both types of ASD.

The discovery that a shared biological process may underpin different forms of ASD is important for understanding the early brain changes that are involved. A common target, like the mTOR pathway, could offer hope for treatments for a wide range of ASDs. However, to translate these benefits to the clinic, further research is needed to understand whether a treatment that is effective in fetal cells would also benefit people with autism.