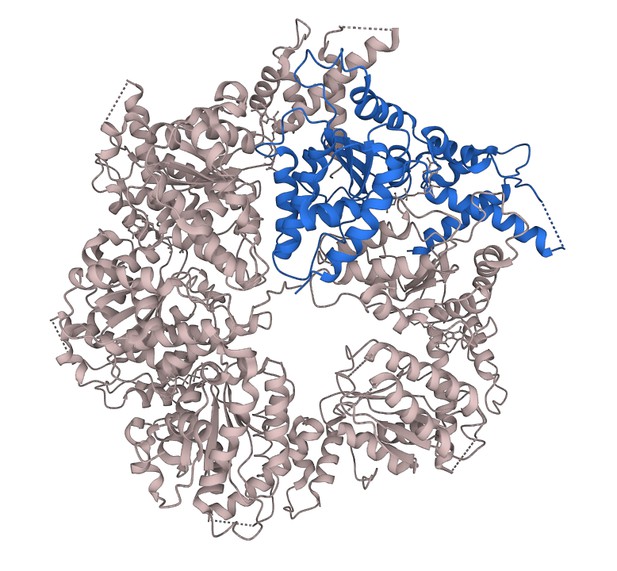

Structure of the human ATAD1 protein. Image credit: PDBe-KB consortium, PDBe-KB: collaboratively defining the biological context of structural data, Nucleic Acids Research, Database Issue (2022) (CC BY 4.0)

Cancer cells have often lost genetic sequences that control when and how cell division takes place. Deleting these genes, however, is not an exact art, and neighboring sequences regularly get removed in the process. For example, the loss of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN, the second most deleted gene in cancer, frequently involves the removal of the nearby ATAD1 gene. While hundreds of thousands of human tumors completely lack ATAD1, individuals born without a functional version of this gene do not survive past early childhood. How can tumor cells cope without ATAD1 – and could these coping strategies become the target for new therapies?

Winter et al. aimed to answer these questions by examining a variety of cancer cells lacking ATAD1 in the laboratory. Under normal circumstances, the enzyme that this gene codes for sits at the surface of mitochondria, the cellular compartments essential for energy production. There, it extracts any faulty, defective proteins that may otherwise cause havoc and endanger mitochondrial health. Experiments revealed that without ATAD1, cancer cells started to rely more heavily on an alternative mechanism to remove harmful proteins: the process centers on MARCH5, an enzyme which tags molecules that require removal so the cell can recycle them. Drugs that block the pathway involving MARCH5 already exist, but they have so far been employed to treat other types of tumors. Winter et al. showed that using these compounds led to the death of cancerous ATAD1-deficient cells, including in human tumors grown in mice.

Overall, this work demonstrates that cancer cells which have lost ATAD1 become more vulnerable to disruptions in the protein removal pathway mediated by MARCH5, including via already existing drugs. If confirmed by further translational work, these findings could have important clinical impact given how frequently PTEN and ATAD1 are lost together in cancer.