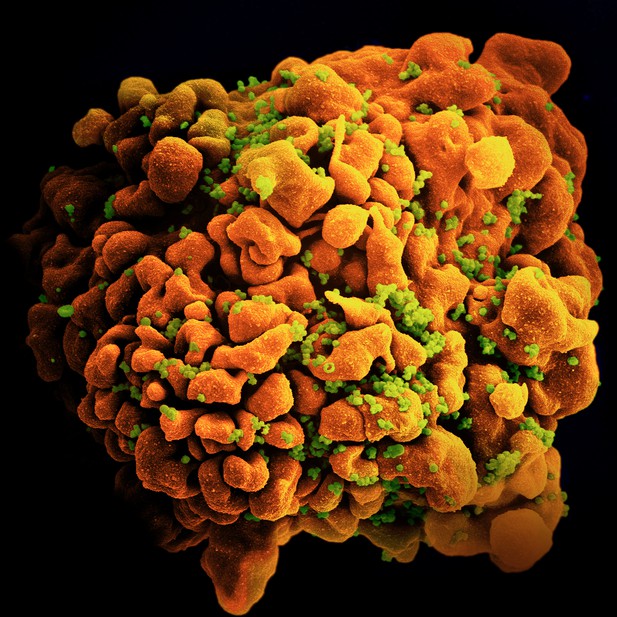

An immune cell infected with HIV. Image credit: National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (CC BY 4.0)

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) affects millions of people across the world, and has caused over forty million deaths. HIV attacks the immune system, eventually leading to lower levels of immune cells, which prevent the body from fighting infections. One of the early effects of HIV infection is inflammation, an immune process that helps the body remove foreign invaders like viruses. Unfortunately, long term inflammation can lead to serious conditions like cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Doctors manage HIV using a class of drugs known as antiretrovirals. These drugs reduce the amount of virus in the body, but they cannot eliminate it entirely. This is because, in the early days of infection, copies of the virus build up in certain organs and tissues, like the gut, forming viral reservoirs. Antiretroviral drugs cannot reach these reservoirs to eliminate them, making a cure for HIV out of reach. One way to address this problem is to develop a new class of drugs that can stop the virus from forming these reservoirs in the first place.

Amand et al. wanted to see whether they could reduce the amount of viral reservoirs that form in HIV patients by interrupting a process called inflammasome activation, which occurs early after HIV infection. Inflammasomes are viral detectors that play a role in both inflammation and the formation of viral reservoirs. They activate an enzyme called caspase-1, which in turn activates proteins called cytokines. These cytokines go on to stimulate further inflammation.

Amand et al. wanted to see whether a drug called VX-765, which blocks the activity of the caspase-1 enzyme, could reduce inflammation and stop the formation of viral reservoirs. To do this, Amand et al. first ‘humanized’ mice, by populating them with human immune cells, so they could become infected with HIV. They then infected these mice with HIV, and proceeded to treat them with VX-765 two days after infection. The results showed that these mice had fewer viral reservoirs, lower levels of cytokines and higher numbers of immune cells than untreated mice.

The findings of Amand et al. show that targeting inflammasome activation early after infection could be a promising strategy for treating HIV. Indeed, if similar results were obtained in humans, then this technique may be the road towards a cure for this virus. In any case, it is likely that combining drugs like VX765 with antiretrovirals will improve long term outcomes for people with HIV.