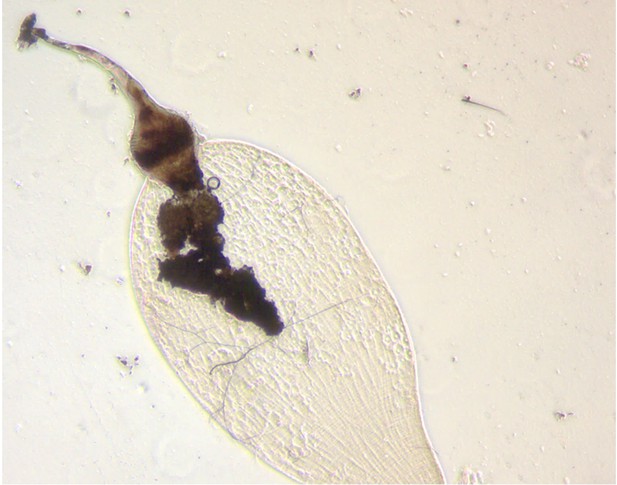

Flea gut with Y. pestis colonization. Image credit: Viveka Vadyvaloo (CC BY 4.0)

Yersinia pestis, the agent responsible for the plague, emerged 6,000 to 7,000 years ago from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, another type of bacteria which still exists today. Although they are highly similar genetically, these two species are strikingly different. While Y. pseudotuberculosis spreads via food and water and causes mild stomach distress, Y. pestis uses fleas to infect new hosts and has killed millions.

A small set of genetic changes has contributed to the emergence of Y. pestis by allowing it to thrive inside a flea and maximise its transmission. In particular, some of these mutations have led to the bacteria being able to come together to form a sticky layer that adheres to the gut of the insect, with this ‘biofilm’ stopping the flea from feeding on blood. The starving flea keeps trying to feed, and with each bite comes another opportunity for Y. pestis to jump host. However, it remains unclear exactly how the mutations have influenced biofilm formation to allow for this new transmission mechanism to take place.

To examine this phenomenon, Guo et al. focused on rcsD, a gene that codes for a component of the signalling system that controls biofilm creation. In Y. pestis this sequence has been mutated to become a ‘pseudogene’, a type of sequence which is often thought to be non-functional. However, the experiments showed that, in Y. pestis, rcsD could produce small amounts of a full-length RcsD protein similar to the one found in Y. pseudotuberculosis. However, the gene mostly produces a short ‘RcsD-Hpt’ protein that can, in turn, alter the expression of many genes, including those that decrease biofilm formation. This may prove to be beneficial for Y. pestis, for example when the bacteria switches from living in fleas to living in humans, where it does not require a biofilm.

Guo et al. further investigated the impact of rcsD becoming a pseudogene inY. pestis, showing that if normal amounts of the full-length RcsD protein are produced, the bacteria quickly lose the gene that allows them to form biofilm in fleas, and cause disease in humans. In fact, additional analyses revealed that all sequenced strains of ancient and modern Y. pestis bacteria can produce RcsD-Hpt, even if they do not carry the same exact rcsD mutation. Overall, these results indicate that rcsD turning into a pseudogene marked an important step in the emergence of Y. pestis strains that can cause lasting plague outbreaks. They also point towards pseudogenes having more important roles in evolution than previously thought.