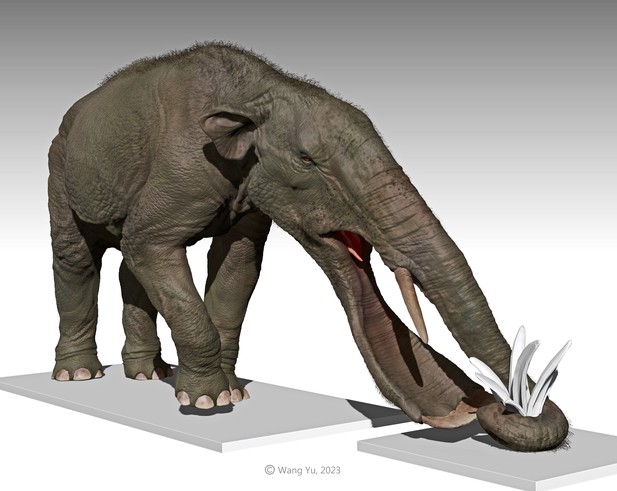

3D reconstruction of Platybelodon, showcasing how these animals could use their flexible trunk to grasp plants before cutting them with their lower tusks. Image credit: Yu Wang (CC BY 4.0)

The elephant’s trunk is one of the most efficient food-gathering organs in the animal kingdom. From large branches to thin blades of grass, it can coil around and bring many types of vegetation to the animals’ strong, short mandibles. This versatility allows elephants to thrive in a range of environments, including grasslands.

Trunks are not the only spectacular feature to emerge in Proboscideans, the family of which elephants are the only surviving group. During the early and middle Miocene (between 23 to 11.6 million years ago), many of these species had dramatically elongated lower jaws; how and why this trait emerged then disappeared is poorly understood. The role that lengthened mandibles and trunks played during feeding also remains unclear.

To address these questions, Li et al. focused on Platybelodon, Choerolophodon and Gomphotherium, which belong to three Proboscidean families that roamed Northern China between 17 and 15 million years ago. Each had elongated lower jaws, but with strikingly distinct lengths and morphologies.

Chemical analyses on enamel samples helped determine which habitat the families occupied, while mathematical modelling revealed how their mandibles tackled different types of plants. Trunk shape was assessed via analyses of the nasal region.

The results suggest that Choerolophodon had mandibles better suited for processing branches and a short, ‘primitive’ trunk. Gomphotherium sported a versatile jaw that could handle both grass and trees, as well as a rather ‘elephant-like’ trunk. The jaw of Platybelodon seemed well-adapted to cut grass, and remarkable bone structures point towards a long, strong and flexible trunk. While modern elephants fully depend on their trunks to eat, morphological constraints suggest that, in these species, the appendage only served to assist feeding (e.g., by pressing down on branches).

All families shared an environment that included grasslands and forests, but analyses suggest that, for a period, Choerolophodon favored relatively closed habitats while Platybelodon spread into grasslands and Gomphotherium navigated both landscapes. This suggests that the evolution of long, strong and flexible trunks is tightly associated with grazing.

About 14 million years ago, a global cooling event led to grasslands expanding worldwide. The fossil record shows the mandibles of Proboscideans starting to shorten after this period, including in the descendants of Gomphotherium that would give rise to modern elephants. The work by Li et al. sheds light onto these evolutionary processes, and the environmental pressures which helped shape the trunk.