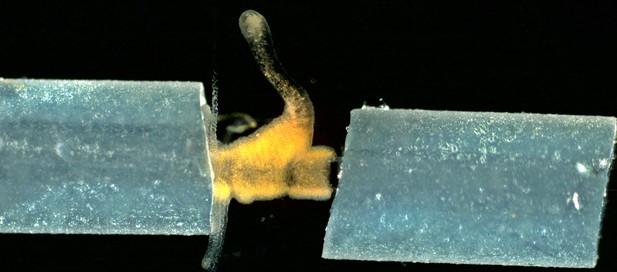

A hydra engrafted with tissue from a hydra that has inherited tumors. Plastic tubes on either side hold the graft in contact with the recipient hydra for several hours to ensure successful transfer. Image credit: Océane Rieu (CC BY 4.0).

Parasites live on or inside host organisms and rely on them for survival. To increase their chances of surviving and spreading, many parasites manipulate their hosts, changing characteristics such as how the host looks, behaves or reproduces. Abnormal tissues growths (known as tumors) can also manipulate their host to fulfil their own needs. For example, some tumors trigger growth of new blood vessels to increase their access to oxygen, nutrients, and to enable them to spread to other organs in a process known as metastasis. In rare cases, tumors can even spread between hosts, much like parasites.

The tiny freshwater animal Hydra oligactis can develop long-term tumors that are passed from one generation to the next. Intriguingly, hydras with these tumors grow more tentacles than those without, helping them to catch more food. This increases their ability to reproduce, which could potentially help to pass tumors on to other hydra hosts.

Boutry et al. aimed to explore whether long-term tumors are directly responsible for increasing the number of hydra tentacles and how they affect tumor transmission. To do so, the researchers tracked tentacle development in hydra with long-term tumors that are passed down over generations and those with spontaneous tumors, which are not transmissible. This revealed that hydras with long-term transmissible tumors develop significantly more tentacles than their healthy counterparts. Notably, hydras with spontaneously occurring tumors did not exhibit this trait.

Next, Boutry et al. transplanted tumor tissues from hydra with long-term tumors or spontaneous tumors onto healthy hydra. Only the long-term transmissible tumor tissue triggered additional tentacle development in previously healthy hosts. This suggests that the tumors have evolved the ability to manipulate host tissue development. Moreover, extra tentacles significantly improved feeding efficiency, leading to higher reproductive rates. Since hydra reproduce by producing genetically identical clones, a higher reproductive output translates into more opportunities for tumor cells to spread.

The findings of Boutry et al. provide the first evidence that transmissible tumors can actively reshape their host’s body structure to benefit their own transmission, suggesting they may have evolved sophisticated strategies to persist and proliferate. Future research could investigate the genetic and biochemical mechanisms underlying this ability. Understanding these processes may offer new insights into the evolutionary dynamics of tumors and identify any similarities with parasitism.