Image credit: Mariana Rodriguez (CC BY 4.0)

You are attending a talk at a conference, eyes straight ahead and fixed on the speaker… yet you may in fact also be covertly monitoring your phone, hoping for a long-awaited message to flash on the screen. This ability to focus on something without directly looking at it is called spatial attention. It plays an essential role in everyday tasks, such as spotting keys on a cluttered desk or noticing when a traffic light changes.

Overlapping brain circuits control spatial attention and eye movements, creating tight links between the two processes. For example, shifting your gaze towards a specific location automatically leads you to pay at least partial attention to what unfolds at this spot. Whether the reverse is true, however, is less clear. In other words: when we are paying attention to something without looking at it, is our brain set to move our eyes towards this location?

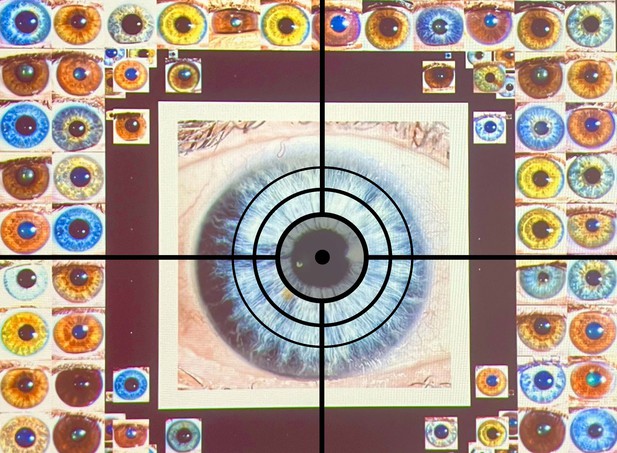

To explore this question, Goldstein et al. designed a visual task that allowed them to track human participants’ attention and eye movements moment by moment, and to unpick various factors affecting these processes. The volunteers fixed their gaze on the center of a screen, knowing that they also needed to pay attention to a certain location at the periphery where a cue was set to appear. The color of the cue determined whether the participants would then need to shift their gaze either towards or away from it – for example, they were instructed to look directly at a green cue but away from a magenta one.

These analyses showed that participants needed about 30 milliseconds less time to program an eye movement toward the cue – that is, to shift their gaze towards the location that they were already covertly monitoring. Such difference in processing time suggests that eye movements are biased towards the location on which attention is directed, but that this preference can still be overridden quickly.

By refining our understanding of the mechanisms underpinning attention, the findings by Goldstein et al. may help us better understand conditions like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, where the brain struggles to engage and disengage with stimuli effectively.