Our societies require drastic and urgent action to respond to the devastating consequences of climate change and ecological destruction. Universities are in a unique position to lead such actions, yet many fail to do so. Bureaucracy, loss of academic freedom and perceived lack of expertise and power are cited as some of the main reasons by many academics. In their article published in 2023, researchers Anne Urai and Clare Kelly propose a new way to overcome some of these challenges based on the framework of ‘Doughnut Academia’, suggesting seven principles for rethinking the norms of scientific practice. Based on the immense interest their article sparked, they designed a workshop to spark climate action amongst academics, which they summarised in their latest preprint. We followed up on their mission to activate academics in this interview.

Anne Urai (left) and Clare Kelly (right)

Please remind readers of the basic ideas put forward in your eLife article in 2023.

Our work centres around the question: Why are so many scientists silent about the climate and biodiversity crises when the impacts are increasingly perceptible? What is it about academic norms that makes people keep their heads down?

In the summer of 2022, we met as fellow neuroscientists concerned and frustrated about this issue. Our realisation was that there were systemic barriers to action. This required us to zoom out and look at the structures and unspoken assumptions that underlie academic culture: assumptions such as the belief that growth – i.e., more papers, more students, more grants – is always good, that cultivating competition and rewarding individuals brings out the best science, and that universities should be run as corporations. We had both been inspired by Kate Raworth’s book Doughnut Economics, which identifies similar hidden assumptions at the heart of economics. Raworth proposes new ways of thinking about our economy so that we can meet everyone’s needs while respecting our planet’s boundaries. This framework became the starting point for designing our own ‘Doughnut Academia’ to answer the question: what would academic practice look like if it were to foster climate action?

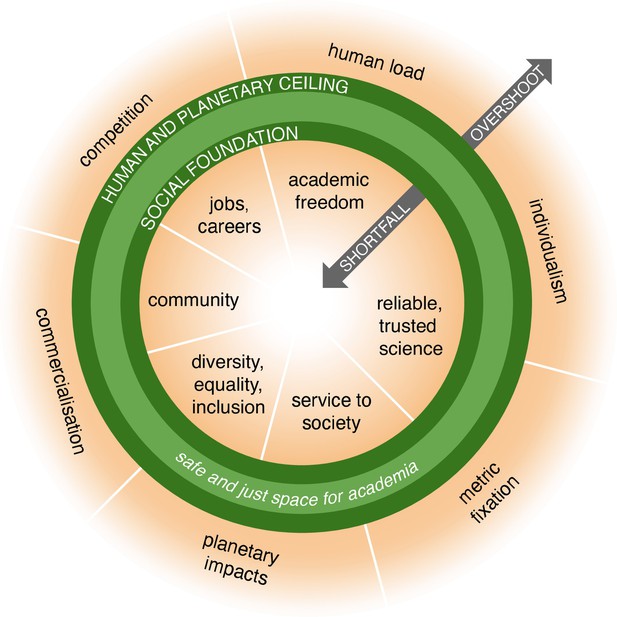

To do this, we applied Raworth’s tools to academia and identified seven dominant, unhelpful norms. To counter these, we propose new ways of thinking about academic communities and our responsibility to act. Importantly, these new norms won’t just help scientists to take climate action – they also have the potential to make our science more equitable, collaborative, distributed and kind.

Doughnut academia. Adapting the “doughnut” model of economics to the academic world enables us to visualise the inner social foundations that universities should provide and the outer human and planetary boundaries that universities need to avoid overshooting. Note that the ordering of elements within the inner and outer rings is random; there is no direct pairing between foundations and ceilings. Adapted from Raworth, 2017 and published in Urai and Kelly, 2023, under a CC-BY-SA license.

What happened after the article was published?

We initially received several emails and positive responses from like-minded colleagues who found our work helpful, but we had not considered further concrete actions. A turning point came when Anne was invited by Fernando Racimo – the first author on another eLife article, The biospheric emergency calls for scientists to change tactics – to conduct a workshop with the Sustainability Committee at his institute in Copenhagen. This encourages us to turn the materials into a structured workshop, which guides participants through a series of activities intended to encourage them in climate action – within their institutions or other scientific bodies, such as professional societies.

In terms of workshops, seminars and so on, what has worked well and/or pleasantly surprised you?

So far, we have given workshops to quite a few different audiences. We have sometimes been pleasantly surprised at the level of sincere and enthusiastic engagement: for example, one of our first workshops, at the Computational Cognitive Neuroscience conference in Oxford, was oversubscribed. It has been fantastic to see the willingness of friends and colleagues to help with the facilitation, often drawing on and sharing their own activist experience. We have been impressed especially by the energy of students, who bear the heaviest burden of the uncertainties of academic careers and the intergenerational injustice of the planetary crisis, and often express feeling quite powerless in the larger systems.

What has not worked so well and/or unpleasantly surprised you?

While some workshops have been full, participation in others has been scant. This may be a symptom of the barriers to taking climate action that many of our colleagues’ experience, not least of which is having sufficient time in their day. In bleaker moments, we wonder if many academics are too comfortable and shielded from the impacts of the climate crisis to feel responsibility for action.

For workshops that have gone well, it is unfortunately difficult to measure and assess their impact. We are limited in our ability to track participants’ actions, and even if we could, it would be impossible to cleanly estimate the effect of this one-time intervention on people’s thoughts and actions, particularly where those may occur far into the future.

Finally, we have noticed that many people are inspired by our work but are not sufficiently empowered to host their own workshops. In our new preprint, we try to change this in the hope that the ideas and materials can be useful beyond the workshops that we are personally able to give.

What are your main tips for running a workshop?

Be prepared! Spend time thinking about the workshop structure. How much time do you have? What activities will the participants complete? How can you avoid getting stuck on listing and discussing the many barriers that must be overcome and instead move participants towards envisioning a positive future and taking concrete actions to realise it? Identify your audience beforehand – are they already engaged, or might they consider the climate crisis someone else’s problem to solve? – and adapt your structure and activities relative to the audience. Practice your talk, and don’t be afraid to get personal – your own journey to climate action can be more inspiring to others than you think. Finally, try to make space for a social gathering afterwards, where the best ideas often emerge. Our preprint has many more recommendations for a successful workshop.

Most importantly, don’t be afraid to dive in. Get in touch with us to share how your workshop went!

In the preprint [page 14], you mention type A, type B and type C audiences – please tell us more about these types of audiences.

Yes, identifying your audience workshop is very important. A type A audience is already engaged – they understand the urgency and are motivated to act. You are “preaching to the choir,” so a workshop for this audience should focus on opportunities for action and leverage points for change within an organisation or community.

A type B “tell me more” audience is not yet actively engaged, nor are they convinced that climate action is their responsibility. A workshop for this audience might leverage their primary identity as scientists to build a sense of empowerment, confidence and community and to identify concrete stepping stones or “easy wins” that can build toward more ambitious actions.

A type C audience contains reluctant, “what am I doing here?” participants. Although this audience can present a challenge and the potential for social friction, don’t underestimate the potential impact of exposure to the topic from a trusted messenger. Simply by breaking the “climate silence”, you may give license to others to follow suit or even find unexpected allies.

You also mention something called a “climate handshake” [page 20] – what is this?

Everyone will have heard about the carbon footprint – the emissions that result from personal lifestyle choices such as food, travel and consumer products. When we talk about climate action, this is often the first and only thing people mention – “I know! I am already taking the train to my next conference!”. While large-scale consumer behaviour change is important for shifting our societies into sustainable norms, personal carbon footprint reduction is a limited way to contribute. After all, dropping dead will eliminate your personal carbon footprint to zero – but this would not in the slightest affect the larger structural problems that are responsible for high-emissions lifestyles.

So, from environmental psychology, we borrow the term “climate handshake” to denote the impact individuals can have on others. These can take place through conversations with friends, family and neighbours, but also in the workplace – especially in communities like classrooms and conferences.

Such “network effects” can ripple out and multiply through social networks, leading to shifts in social norms – just think of the widespread adoption of preprints across scientific communities in the last decade. Ultimately, these can create a demand for policy change, which, in turn, creates the conditions for low-carbon lifestyles as the default.

Another way to think about this: consider the carbon footprint as the effect of your own activities, disconnected from the larger social networks you are embedded in. The climate handshake considers your network effect explicitly, helping individuals consider where their leverage points may be the largest. This can, for instance, be in teaching students, talking to university governance or policymakers, or lending your voice to larger movements aimed at transformative structural change.

You are both based in Western Europe – has there been any impact outside Western Europe?

So far, we have only heard from people in the US and Europe (see the map at https://anneurai.net/doughnut-academia/), but we would love to see these ideas spread further and to hear from people in other parts of the world – and we hope that our new preprint can support this goal.

Has your activism had an impact – positive or negative – on your careers?

This depends a lot on your definition of a positive career impact! If defined in a broad sense of finding community and solidarity and working collectively to inspire a better university, then it certainly has. If it is defined in the traditional and narrow sense as helping us to get lots of papers, funding, keynote lectures, prizes or promotions, then it has not. Or, if we are optimistic, not yet: we certainly hope to see a future where critical analysis and activism are acknowledged and celebrated within our current academic career paths.

We try to bring these lessons into our own research and teaching, which can be challenging given the existing expectations and norms of the systems we work in. That said, this work has opened many doors for us and connected us with new colleagues in different departments, people in university leadership, fellow activists and students. This has been immensely rewarding, and sometimes it feels like doughnut academia may prove to be the most impactful thing we do in our careers.

If there was one message you wanted to get across or one piece of advice you would give someone who was hoping to make a difference, what would it be?

Anne: Embrace uncertainty – you may never know the impacts of your actions, but that doesn’t mean they are not important. The scientist in me has found it hard to let go of precisely wanting to quantify the outcomes of what I do, and I continue learning to take a more holistic lens on different ways to have an impact in my work.

Clare: We are living through uncertain and unsettling times in which it can feel like there are many other pressing issues besides the planetary crisis. In the US and elsewhere, rights and freedoms that have long been taken for granted are under threat. Science itself is under threat. Under these conditions, speaking up alone can seem impossible, even dangerous – never has community and solidarity been more important. As a cherished Irish saying goes, “ní neart go cur le chéile” – there is no strength without unity. Look for that solidarity everywhere – you will often find it in the most surprising places. Also, for sustenance, read Rebecca Solnit’s book “Not too late”, or her article published in the Guardian!

Interview by Helga Groll, Associate Features Editor, eLife.