Herpes simplex type 2 virus deleted in glycoprotein D protects against vaginal, skin and neural disease

Figures

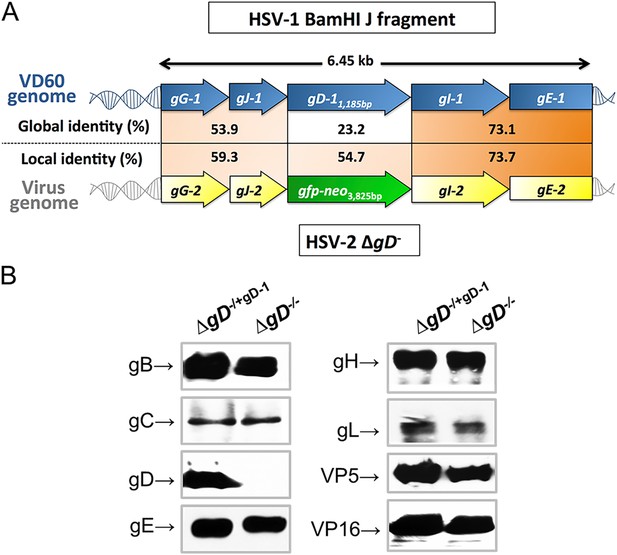

Characterization of the ΔgD−/− virus.

(A) Alignment of the upstream and downstream regions of gD located within the HSV-1 BamHI J fragment encoded in VD60 cells and within the genome of ΔgD−/− using LALIGN (ExPASy) (Myers and Miller, 1988). Global alignments assess end-to-end sequences and local pairwise alignments search for regions with high identity. (B) Western blots of dextran gradient-purified virus isolated 24 hr after infection of VD60 (ΔgD−/+gD−1) and Vero (ΔgD−/−) cells. Protein expression was assessed for viral glycoproteins B (gB, UL27), gC (UL44), gD (Us6), gE (Us8), gH (Us22), gL (UL1), VP5 (UL19) and VP16 (UL48).

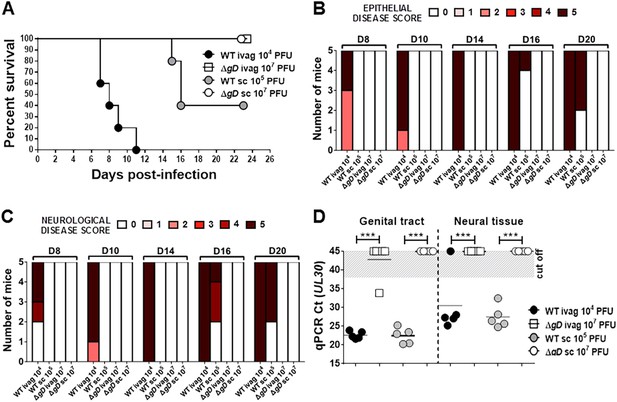

HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 is attenuated in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice.

(A) Survival of SCID mice inoculated with up to 107 pfu of HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 or up to 105 pfu of the parental HSV-2(G) strain either intravaginally (ivag) or subcutaneously (sc). Statistical significance was measured by log-rank Mantel–Cox test; **p < 0.01 for ΔgD and WT after ivag inoculation. (B) Epithelial and (C) Neurological disease scores for SCID mice inoculated with the different viruses at indicated doses. (D) HSV-2 DNA (qPCR, UL30 gene) in genital tract and neural tissue samples at day 5 post-virus inoculation. The Ct cut off was determined with HSV-uninfected naïve samples. Statistical significance was measured by two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test for (B, C and D); ***p < 0.001. HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 and its parental strain are abbreviated as ΔgD and WT, respectively.

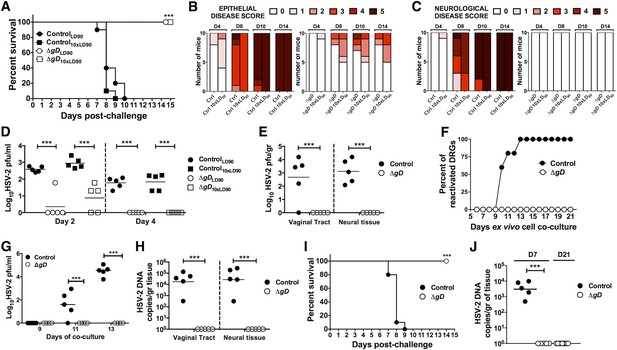

Vaccination with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 protects mice against intravaginal lethal challenge.

C57BL/6 mice were subcutaneously primed and boosted 3 weeks apart either with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 or VD60 cell lysate (Control). 21 days after boost, mice were challenged with an LD90 of wild-type HSV-2(4674) or 10 × LD90. (A) Survival, (B) Epithelial and (C) Neurological disease scores were followed daily after challenge. (D) Viral titers in vaginal washes at days 2 and 4 after challenge (n = 10 mice pooled two per group, lines indicate means). (E) Viral titers in vaginal and neural tissue (including the dorsal root ganglia, DRG) at day 5 after challenge (n = 5, lines indicate means). (F) Ex vivo reactivation of neural tissue obtained from challenged mice (n = 5 per group). (G) HSV-2 pfu in the media of ex vivo reactivated neural tissue obtained from challenged mice (n = 5 mice per group, lines indicate means). (H) HSV-2 DNA (qPCR, US6 gene) of genital tissue and neural tissue at day 5 after challenge (n = 5, lines indicate means). (I) Survival of BALB/c mice that were primed, boosted and challenged as the C57BL/6 mice described above. (J) HSV-2 DNA (qPCR, US6 gene) in Control- and ΔgD-vaccinated BALB/c neural tissue at day 7 (n = 5, lines indicate means) and ΔgD-vaccinated BALB/c neural tissue at day 21 (n = 9, lines indicate means) after challenge. HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated group vs Control-vaccinated group were compared by log-rank Mantel–Cox test (A, I), two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test (D, E, G, H) or unpaired t-test (J); ***p < 0.001. HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 and Control are abbreviated as ΔgD and Ctrl, respectively.

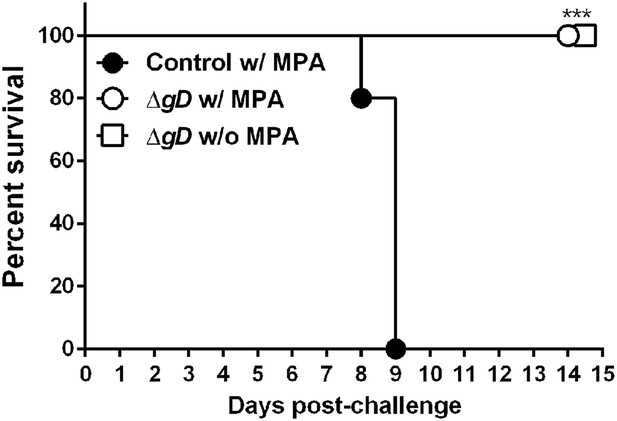

ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated cycling mice are protected against intravaginal HSV-2 challenge.

C57BL/6 mice were treated (w/MPA) or not (w/o MPA) with medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 5 days previous to subcutaneous prime and boost 3 weeks apart either with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 (ΔgD) or VD60 cell lysate (Control). 16 days after boost, all mice were treated with MPA and 5 days later challenged intravaginally with an LD90 of wild-type HSV-2(4674) (n = 5 mice per group). Statistical significance was measured by log-rank Mantel–Cox test; ***p < 0.001, treatments vs Control.

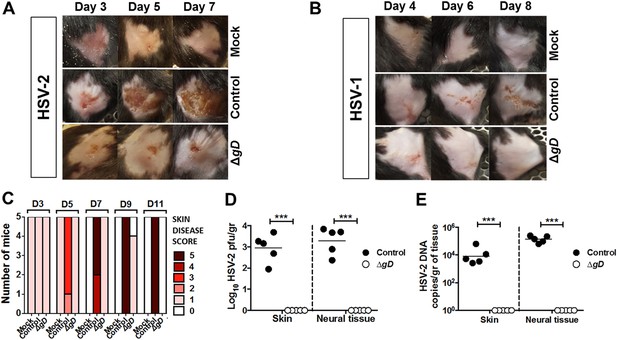

Vaccination with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 protects mice infected with HSV-2 and HSV-1 in a skin scarification model.

Mice were subcutaneously primed and boosted 3 weeks apart either with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1, Control VD60 cell lysate or PBS. 3 weeks later, mice were depilated and challenged in the flank skin with PBS (mock), (A) 5 × 104 pfu HSV-2(4674) or (B), 1 × 107 pfu HSV-1(17). Representative images are shown. (C) Skin disease scores for HSV-2(4674)-challenged mice at days 3–11. (D) Viral titers from biopsies of skin or neural tissue obtained on day 6–7 (Control mice) and day 14 (HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice) (n = 5 mice per group, lines indicate means). (E) HSV-2 DNA (qPCR, US6 gene) in skin biopsies and neural tissue of Control mice (day 6–7) and HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice (day 14) challenged with virus (5 mice per group, lines indicate means). Statistical significance was measured by two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test (D and E); ***p < 0.001, ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated group vs control group. HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 is abbreviated as ΔgD.

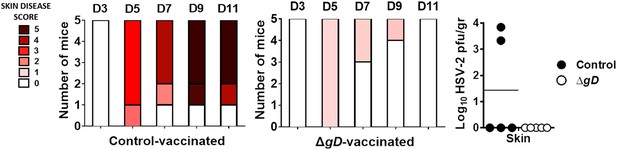

Vaccination with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 protects mice infected with HSV-1 in a skin scarification model.

Mice were subcutaneously primed and boosted 3 weeks apart either with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 or Control VD60 cell lysate. 3 weeks later, mice were depilated and challenged in the flank skin with1 × 107 pfu HSV-1(17). Skin disease scores shown for challenged mice at days 3–11. Viral titers from biopsies of skin obtained on day 7–8 (Control mice) and day 14 (HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice) (n = 5 mice per group, lines indicate means). Statistical significance was measured by unpaired t-test.

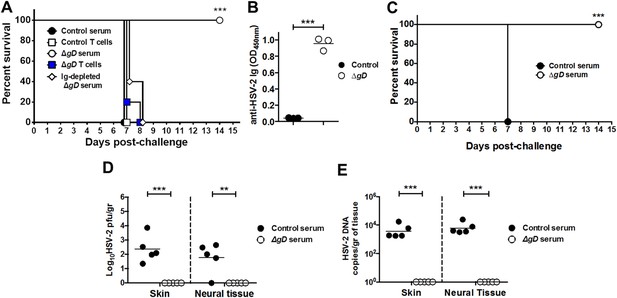

Serum from HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice protects naïve mice against HSV-2 intravaginal and skin challenge.

Mice were subcutaneously primed and boosted 3-weeks apart either with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 or VD60 cell lysate (Control). 21 days later, blood and spleen were collected for serum and T cell purification and transferred intraperitoneally and intravenously, respectively, into naïve wild-type C57BL/6 mice. 24 hr and 48 hr after serum and T cell transfer, respectively, mice were challenged intravaginally with LD90 of HSV-2(4674) and followed for survival (n = 5 mice per group). Serum immunoglobulins were depleted using a Protein L column (A). (B) Transferred anti-HSV-2-antibodies were assessed by ELISA in vaginal washes of recipient mice (washes pooled from five mice in three independent experiments). (C) Pooled serum from Control- or HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice was transferred into naïve wild-type C57BL/6 mice. 24 hr after serum transfer, mice were depilated in the flank skin and challenged with HSV-2(4674) and followed for survival (n = 5 mice per group). (D) Viral titers in skin biopsies and neural tissue of mice receiving Control-serum (day 7) and ΔgD−/+gD−1-serum (day 14) (n = 5 mice per group). (E) HSV-2 DNA (qPCR, US6 gene) in skin biopsies and neural tissue of mice receiving Control-serum (day 7) and ΔgD−/+gD−1-serum (day 14) (n = 5 mice per group). Statistical significance was measured by log-rank Mantel–Cox test (A and C), t-test (B) and two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (D); **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, treatment vs control. HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 is abbreviated as ΔgD.

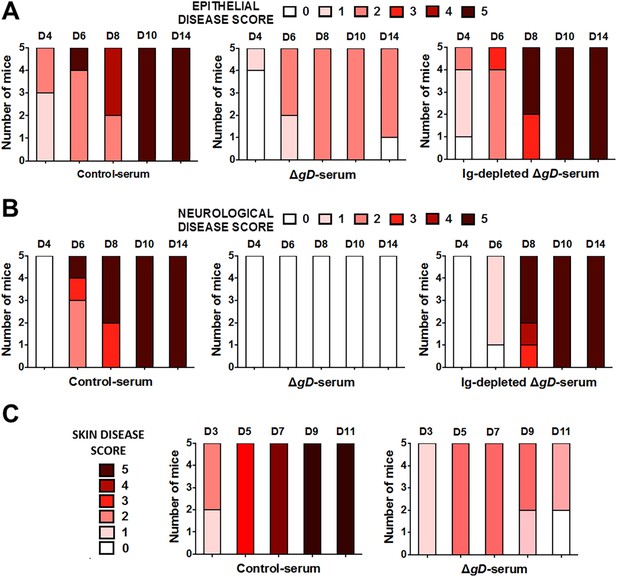

Serum from HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice protects naïve mice against epithelial and neurological disease after HSV-2 intravaginal and skin challenge.

Serum from Control- (VD60 cell lysate), ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice, or ΔgD−/+gD−1 serum depleted of immunoglobulins using a Protein L column was transferred intraperitoneally into naïve wild-type C57BL/6 mice. 24 hr later, mice were challenged intravaginally with LD90 of HSV-2(4674) and followed for (A) epithelial and (B) neurological disease (n = 5 mice per group). (C) Serum from Control- or HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice was transferred intraperitoneally into naïve wild-type C57BL/6 mice. 24 hr later, mice were depilated and challenged in the flank skin with HSV-2(4674) and followed for epithelial disease.

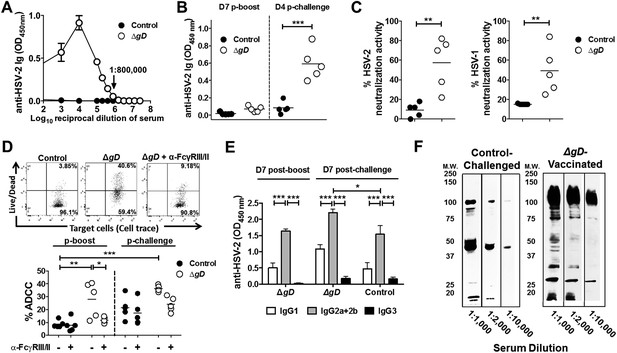

Vaccination with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 induces protective mucosal antibodies targeting multiple HSV proteins with ADCC activity.

(A) Anti-HSV-2 antibodies detected by ELISA in serum samples at day 7 post-boost in mice subcutaneously primed and boosted 3-weeks apart with ΔgD−/+gD−1 or VD60 lysate (Control) (4 independent pools of serum from 5–10 mice each, results shown as means ± SD). (B) Anti-HSV-2 antibodies detected by ELISA in vaginal washes at day 7 post-boost and day 4 post–challenge with HSV-2(4674) (n = 5 mice per group, lines indicate means). (C) In vitro neutralizing activity of serum antibodies (1:5 dilution) obtained from HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1- or Control-vaccinated mice against HSV-2 (left) and HSV-1 (right) (n = 5 mice per group, lines indicate means). (D) Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) using mouse splenocytes, HSV-2-infected Vero cells and serum obtained either from Control- (VD60 cell lysate) or HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice conducted in the absence or presence of anti-CD16/CD32 Ab to FcγRIII and FcγRII. % ADCC is defined as the percentage of dead (Live/Dead+) target cells within HSV-2 GFPHigh positive cells. A representative dot blot is shown in the upper panel and lower panel shows results for five mice per group (lines indicate means). (E) Isotype of anti-HSV-2 serum antibodies obtained from five mice each that were either HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated and HSV-2(4674)-challenged or Control-vaccinated and HSV-2(4674)-challenged (results shown as means ± SD). (F) Western blots of cellular lysates infected with HSV-2(4674) and probed with dilutions of sera obtained from VD60 lysate-vaccinated and then subsequently infected mice (Control-Challenged) or dilutions of sera from HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice 7 days post boost (ΔgD-Vaccinated); blots are representative of five independent experiments. HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated groups were compared to control-vaccinated mice by two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test (A, B, D and E) and unpaired t-test (C); *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 is abbreviated as ΔgD.

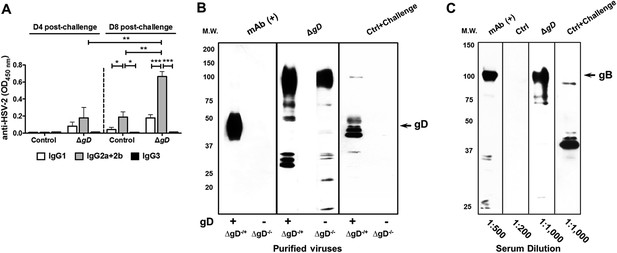

Characterization of vaginal wash and serum antibodies.

(A) Isotypes of anti-HSV-2 antibodies in vaginal washes obtained at day 4 and day 8 post intravaginal challenge in mice that were immunized with HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 (ΔgD) or VD60 cell lysate (Control). Antibody responses are shown as means ± SD (n = 5 per group) and were compared by two-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (B) Western blots with sucrose gradient-purified ΔgD−/+gD−1 and ΔgD−/− viruses (equivalent particle numbers based on a Western blot for VP5) probed with an anti-gD mAb (mAb (+)), sera from HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice day 7 post-boost (ΔgD) or sera from VD60 lysate-vaccinated mice day 7 post-intravaginal challenge with HSV-2(4674) (Ctrl + Challenge). (C) Western blots with purified recombinant glycoprotein B-1 (2 μg per lane) probed with an anti-gB mAb (mAb (+)), sera from VD60 lysate -vaccinated mice (Ctrl), HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated mice day 7 post boost (ΔgD) or VD60 lysate-vaccinated mice day 7 post-intravaginal challenge with HSV-2(4674) (Ctrl + Challenge).

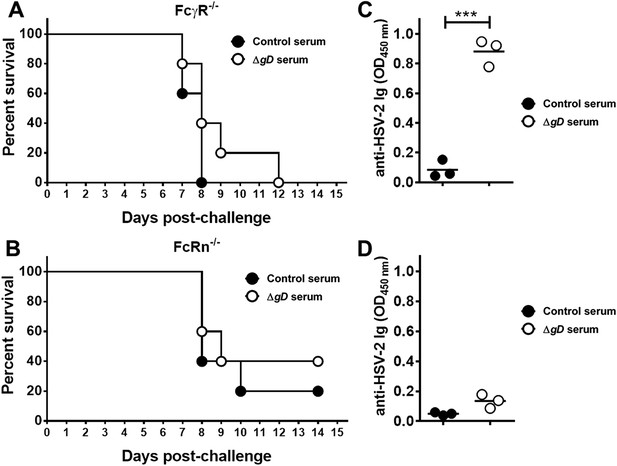

Antibody-mediated protection requires FcγR and FcRn expression.

Survival of (A) FcγR−/− and (B) FcRn−/− mice that were either transferred serum obtained from Control- (VD60 cell lysate) or HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated wild-type mice and then challenged intravaginally with HSV-2(4674) (n = 5 mice per group). Detection of HSV-specific Abs by ELISA in pooled vaginal washes (n = 3 pools) of (C) FcγR−/− and (D) FcRn−/− mice receiving serum (intraperitoneally) from control- (VD60 cell lysate) or HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated wild-type mice. Survival curves were compared using log-rank Mantel–Cox test (A and B) and antibody titers using unpaired t-test (C and D); ***p < 0.001. HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1 is abbreviated as ΔgD.

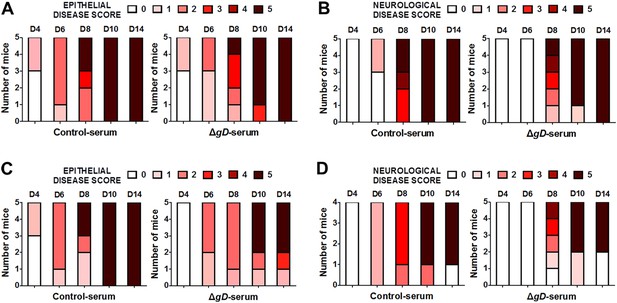

Antibody-mediated protection requires FcγR and FcRn expression.

Epithelial and neurological disease scores in (A, B) FcγR−/− and (C, D) FcRn−/− mice receiving serum from control- or HSV-2 ΔgD−/+gD−1-vaccinated wild-type mice and then challenged intravaginally with HSV-2(4674) (n = 5 mice per group).