More effective drugs lead to harder selective sweeps in the evolution of drug resistance in HIV-1

Figures

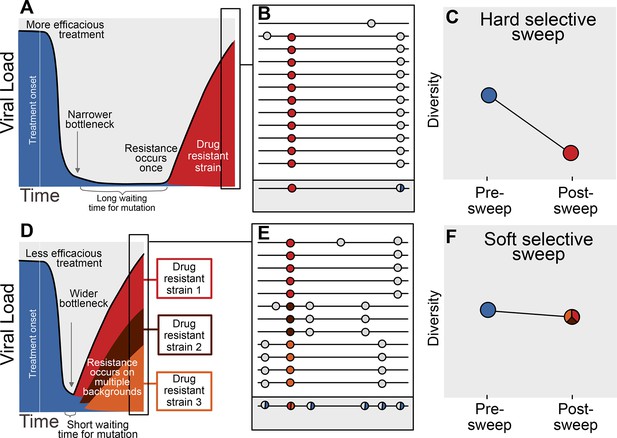

Prediction of drug resistance acquisition with more and less effective treatments.

Among patients treated with more effective treatments (top), we predict HIV populations to have a lower probability of acquiring resistance per generation. As a result, the population must wait a long time for a beneficial genotype, so when resistance does occur, it will spread through the population in a hard selective sweep before other resistant genotypes emerge (A). Since resistance only occurs on a single genetic background (background mutations in grey), all sequences with resistance will be similar (B) and diversity following this type of selective sweep will be reduced (C). We can use the reduction of diversity to determine that a selective sweep is hard. In patients treated with less effective treatments (bottom), we predict HIV populations should have a higher probability of acquiring resistance per generation, so resistance will be acquired more quickly and selective sweeps of drug resistance mutations will be soft (D). We can detect these soft selective sweeps, because diversity remains high when resistance mutations on different genetic backgrounds rise in frequency simultaneously (E,F).

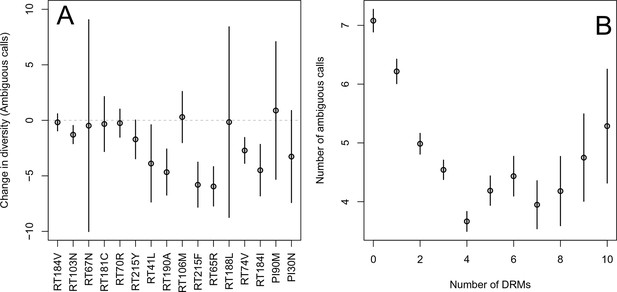

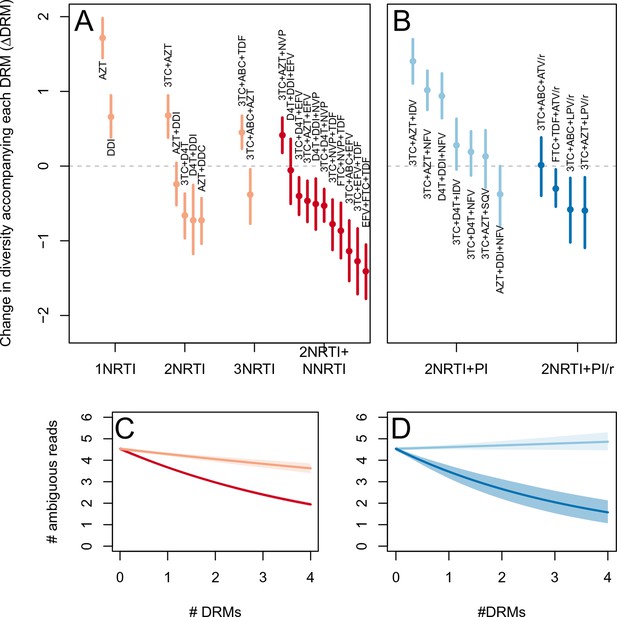

Effect of DRMs on sequence diversity.

(A) For the most common reverse transcriptase and protease mutations, 95% confidence intervals are drawn for the difference in diversity associated with a single derived mutation. For each DRM, the mean diversity among patients with a fixed ancestral state at the focal locus is compared to those patients with that fixed non-ambiguous DRM. All sequences have no additional DRMs. All DRMs occurring at least 5 times with these specifications are included. (B) The effect of multiple DRMs on diversity is shown as the average diversity level of sequences decreases conditional on number of fixed drug resistance mutations present. Means SE are plotted among all patients in the D-PCR dataset.

Diversity and the number of drug resistance mutations by treatment categories.

The relationship between diversity and the number of drug resistance mutations is plotted separated out by the major treatment categories included in our analysis: (A) NRTI(s) without any other drugs, (B) NRTIs with unboosted PI, (C) NRTIs and an NNRTI and (D) NRTIs and PI/r. Data plotted is just the abundant treatment dataset.

Effect of multiple DRMs on sequence diversity separated by subtype.

Average diversity level of sequences are plotted conditioned on number of fixed drug resistance mutations present separately by all the subtypes with more than 100 associated HIV populations. Means SE are plotted among all the D-PCR dataset.

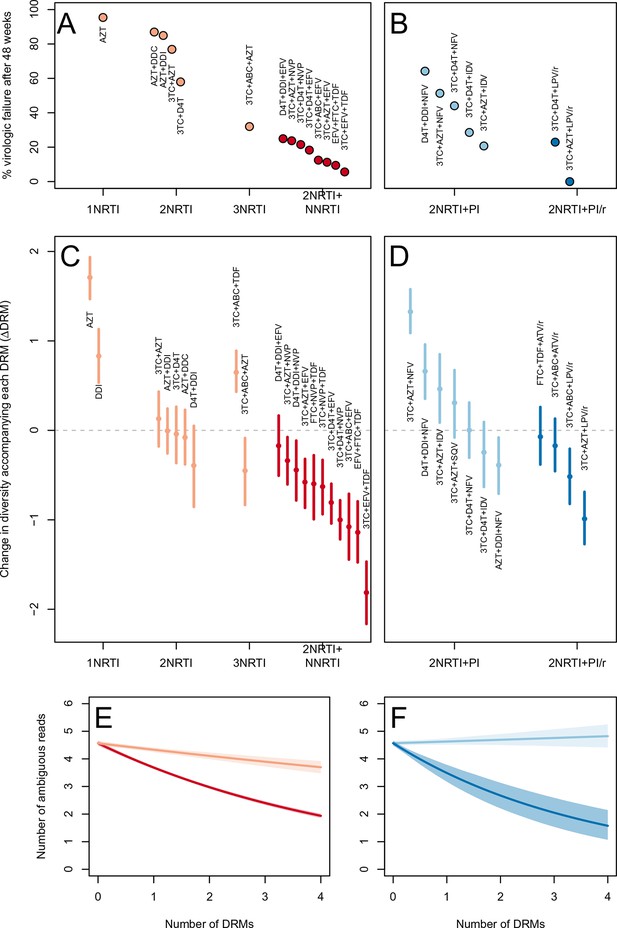

Drug resistance mutations are correlated with diversity reduction differently in different types of treatments.

Treatment effectiveness from literature review (percentage of patients with virologic suppression after ~48 weeks) showed positive correspondence with clinical recommendation among RTI regimens (A) and PI+RTI regimens (B). Diversity reduction accompanying a DRM ( from the GLMM) lower among the more effective and clinically recommended treatments among RTI treatments (C) and RTI+PI treatments (D). 95% confidence intervals are plotted by excluding the highest 2.5% and lowest 2.5% of GLMM random effect fits of the 1000 subsampled datasets and treatments are ordered by mean within treatment categories. Generalized linear model fits show significantly different slopes for NNRTI treatments versus NRTI treatments (E) and PI/r treatments versus PI treatments (F). Confidence intervals are plotted by excluding the highest 2.5% and lowest 2.5% of GLM fits to 1000 subsampled datasets.

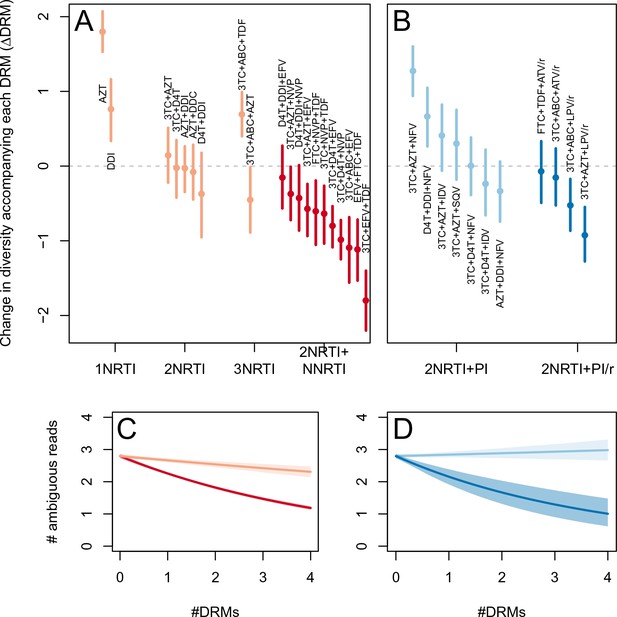

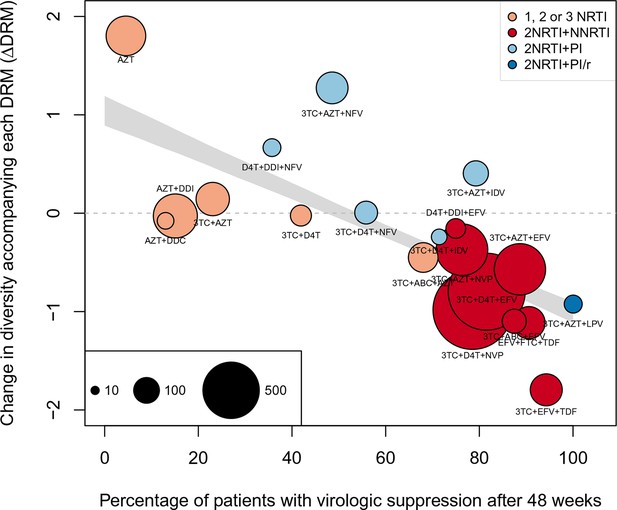

Drug resistance mutations are correlated with diversity reduction differently in different types of treatments when all years are included.

This figure is analogous with Figure 3 from the main text, but in this case, the data include 45 sequences sampled before 1995. The inclusion of these sequences substantially changes the effect of the subsampling procedure, which explains the difference in scales of these figures (see Materials and methods: -thinning to adjust for the effect of year). The figure caption is otherwise shared with Figure 3.

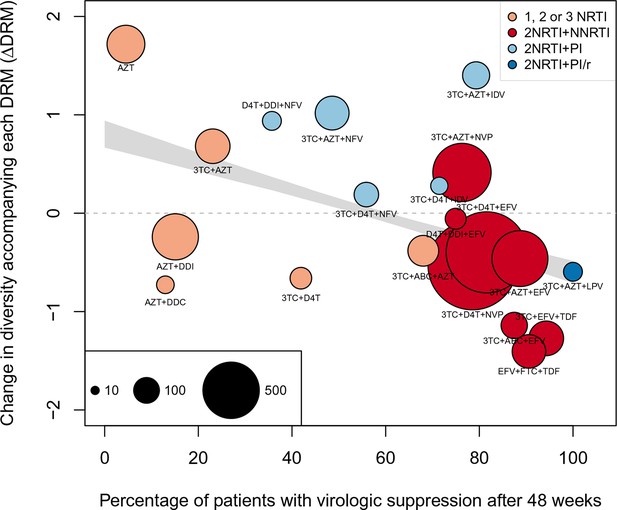

Drug resistance mutations are correlated with diversity reduction differently in different types of treatments with un-truncated data.

This figure is analogous with Figure 3 from the main text, but in this case, the data are not truncated to only include the patients with 4 or fewer DRMs. The figure caption is otherwise shared with Figure 3.

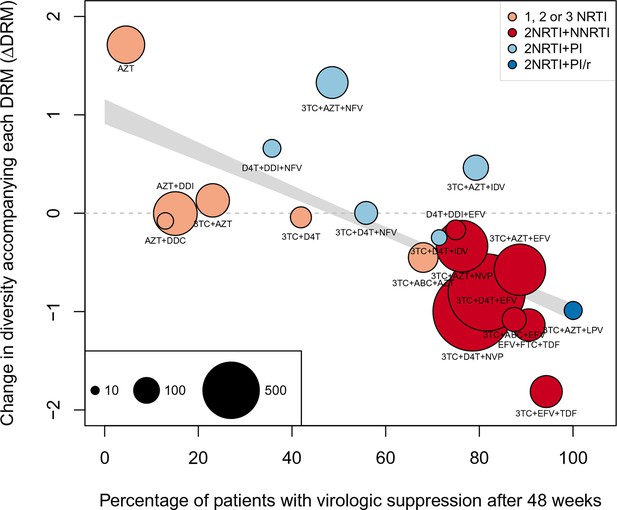

Nonparametric test shows negative correlation between treatment effectiveness and .

Negative relationship between treatment effectiveness (percentage of patients with virologic suppression after ~48 weeks) and as fit within the GLMM among all treatments for which we have recorded effectiveness information. Treatments included are plotted at the mean from GLMMs fit to 1000 iterations of data subsampling. Points for each treatment are sized in proportion to the number of sequences from patients given that treatment (see legend in the lower left), and are colored based on the treatment type (see legend in the upper right). The black line shows the mean effect of treatment effectiveness on from linear regressions fits to the 1000 subsampled datasets and the grey band shows a 95% confidence interval (excluding the top and bottom 2.5% of fits).

Nonparametric test shows negative correlation between treatment effectiveness and when 45 sequences from before 1995 are included.

This figure is analogous with Figure 4 from the main text, but in this case, 45 sequences before 1995 are included in the analysis. The coefficients are taken from the GLMM shown in Figure 3—figure supplement 1 A and B. The figure caption is otherwise shared with Figure 4.

Nonparametric test shows negative correlation between treatment effectiveness and when sequences with any number of DRMs are included.

This figure is analogous with Figure 4 from the main text, but in this case, the data is not truncated to only include the patients with 4 or fewer DRMs. The coefficients are taken from the GLMM shown in Figure 3—figure supplement 2A and B. The figure caption is otherwise shared with Figure 4.

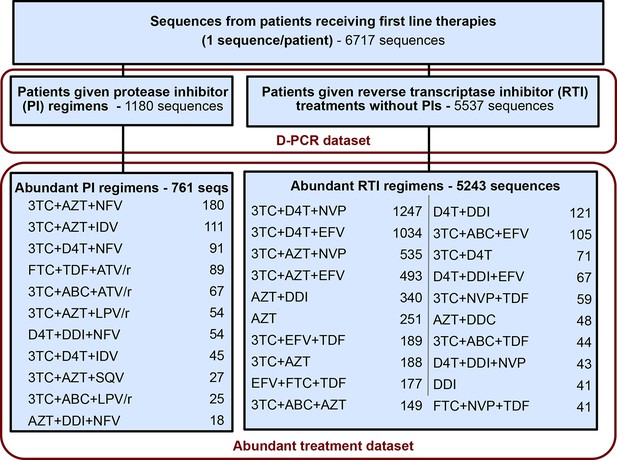

Summary of data subgroups and filtering.

Summary of all sequences from patients receiving first line therapy used throughout the analysis. The dataset is broken down into patients receiving protease inhibitor (PI) therapy with reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTIs) and patients receiving only RTIs. The abundant treatment dataset shows treatments given to many patients within our dataset. For full filtering parameters for the abundant dataset, see Materials and methods: Data collection & filtering. Counts of sequences for each treatment are given.

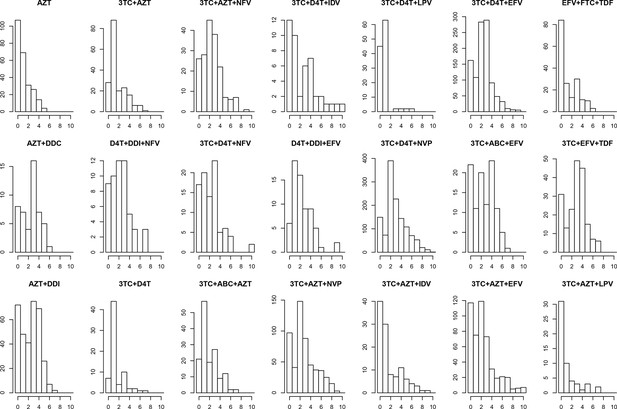

Distribution of number of DRMs by treatment.

The distribution of the number of drug resistance mutations is plotted separated out by the major treatments included in our analysis. The y-axes are not standardized, and show the number of consensus sequences per treatment with each number of fixed DRMs within the abundant treatment dataset.

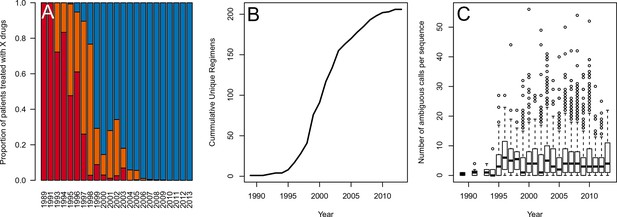

Data is heterogenous with respect to year in terms of the number of drugs per treatment, the diversity of treatments and the number of ambiguous reads per sequence.

(A) Percentage of patients receiving 1, 2 or 3 or more drugs (red, orange and blue bars, respectively) changes over the timecourse of our sampling period. (B) The cumulative number of unique treatment regimens is shown over the course of our sample period. (C) Barplots demonstrating the number of ambiguous amino acids per sequence by year with interquartile ranges. One outlier is excluded for visibility.

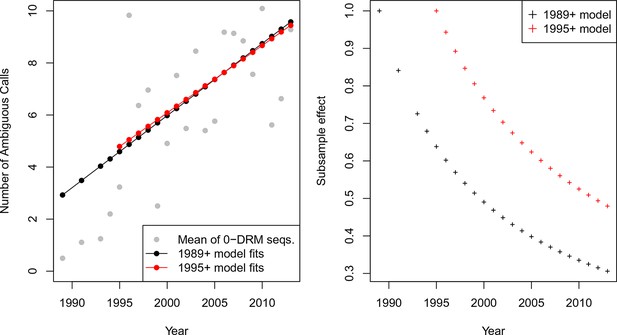

-thinning controls for systematic changes in the called number of ambiguous reads over time A.

The mean number of ambiguous calls has increased over time among sequences with 0 DRMs. Linear model fits predicting the number of ambiguous reads from year among sequences with 0 DRMs are shown in black for sequences from 1989 or later (Equation 1) and red for sequences from 1995 or later (Equation 2). These model fits are used to compute the subsample effect, shown in B.

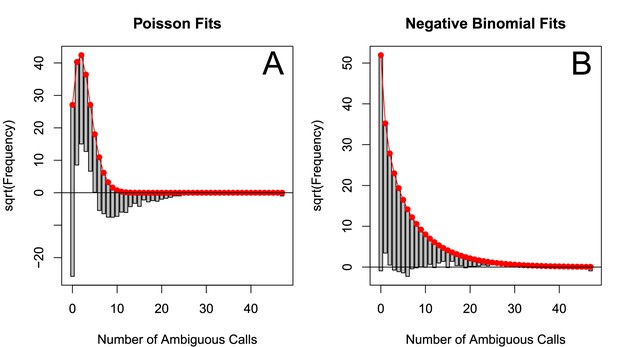

The number of ambiguous reads is approximately distributed according to a negative binomial when p-thinned relative to 1989.

The subsampled number of ambiguous reads (relative to 1989) relative to the best fit Poisson distribution (A) and best fit negative binomial distribution (B). The fits to one particular subsample are plotted, but the graphs are representative. These distributions were fit using vcd (Meyer et al., 2015).

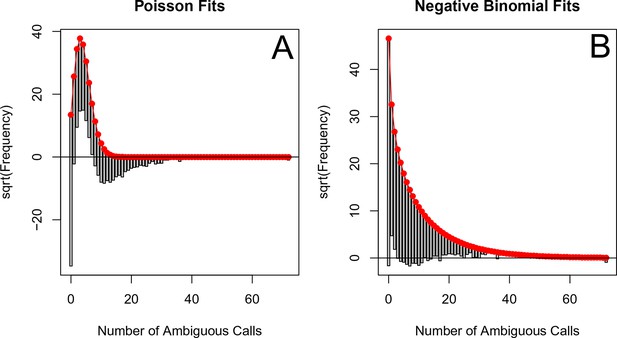

The number of ambiguous reads is approximately distributed according to a negative binomial when p-thinned relative to 1995.

The subsampled number of ambiguous reads (relative to 1995) relative to the best fit Poisson distribution (A) and best fit negative binomial distribution (B). The fits to one particular subsample are plotted, but the graphs are representative. These distributions were fit using vcd (Meyer et al., 2015). Note, many more ambiguous calls are retained with -thinning relative to 1995 as compared to relative to 1989 (See Figure 5—figure supplement 4).

Tables

Model fits for the fixed effects from GLMMs fit to subsampled data. See Materials and methods: Quantifying the relationship between clinical effectiveness and diversity reduction for further explanations of coefficients. Means of model fits for 1000 independent subsamples are reported for the three different subsampling and model-fitting regimes. 95% confidence intervals (excluding the top 2.5% and bottom 2.5% of coefficent fits) are given in parentheses.

| (Intercept) | (Number of DRMs) | (Length) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995+, 4 DRMs | -0.82 | -0.12 | 0.0030 |

| (-0.94,-0.68) | (-0.13,-0.10) | (0.0028,0.0031) | |

| 1995+, All DRMs | -0.88 | -0.083 | 0.0030 |

| (-1.00,-0.76) | (-0.094,-0.073) | (0.0028,0.0031) | |

| 1989+, 4 DRMs | -1.33 | -0.12 | 0.0030 |

| (-1.50,-1.16) | (-0.13,-0.097) | (0.0028,0.0032) |

Coefficients from GLMs fit to subsampled data. See Materials and methods: Quantifying the relationship between clinical effectiveness and diversity reduction for further explanations of coefficient descriptions. Means for 1000 independent subsamples are reported for the three different subsampling and model-fitting regimes. 95% confidence intervals (excluding the top 2.5% and bottom 2.5% of coefficent fits) are given in parentheses.

| (Intercept) | (Length) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995+, 4 DRMs | -0.51 | 0.0025 | -0.21 | -0.053 | -0.27 | 0.013 |

| (-0.62,-0.40) | (0.0024,0.0027) | (-0.23,-0.20) | (-0.070,-0.036) | (-0.36,-0.18) | (-0.009,0.035) | |

| 1995+, All DRMs | -0.66 | 0.0026 | -0.13 | -0.039 | -0.14 | 0.033 |

| (-0.77,-0.56) | (0.0025,0.0028) | (-0.14,-0.12) | (-0.053,-0.026) | (-0.21,-0.096) | (0.019,0.047) | |

| 1989+, 4 DRMs | -1.03 | 0.0026 | -0.22 | -0.047 | -0.27 | 0.016 |

| (-1.18,-0.88) | (0.0024,0.0028) | (-0.23,-0.20) | (-0.069,-0.025) | (-0.39,-0.17) | (-0.013,0.043) |

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Detailed description of treatment effectiveness computation including references.

(A) Detailed description (organized by study) of how we extracted treatment successes versus failures, as well as length of study and viral load limit for each study. Part (B) is a reorganization of (A), but it excludes specific details on how we calculated each number.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.10670.021

-

Supplementary file 2

Detailed description of treatment effectiveness computation including references.

(B) Chart summary (organized alphabetically by treatment) detailing all studies considered for our treatment effectiveness analysis. For each study, we recorded the number of weeks, the virologic load limit under which was considered a ‘‘success,’’ the number of successes and the total number of patients on on-treatment analysis considered.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.10670.022

-

Supplementary file 3

Part (C) is a further summary of the final treatment effectiveness used throughout our analysis.

This supplement has a full reference section describing the studies used.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.10670.023