Sexually dimorphic neuronal responses to social isolation

Figures

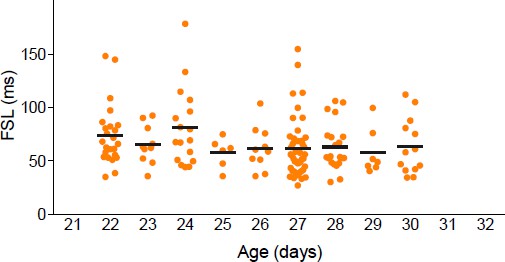

Social isolation alters intrinsic properties of CRH neurons in female, not male mice.

(a) Experimental timeline (top), schematic (middle) showing coronal brain section of PVN (red) with a fluorescent image of tdTomato immunofluorescence (bottom). Panels on right show DIC image with electrode (top), tdTomato cells (middle) and recorded neuron (bottom) (b) Summary bar graphs indicate no difference in FSL for single and group-housed males (left, one-way ANOVA, p=0.9). FSL in single females is significantly longer than group-housed females (one-way ANOVA, p<0.0001). FSL in group-housed females and males are not different (p>0.05). (c) Traces show responses to a single +80 pA depolarizing step (holding potential = −102 mV) in group (dark blue) and single-housed (light blue) males. FSL calculated from the start of the depolarizing pulse (dotted line) to the first spike is plotted for all cells in (c). The relative frequency distributions are overlaid by the relative cumulative distributions. (d) Traces show responses to the same depolarizing step protocol as in (c) but in group (dark orange) and single-housed (light orange) females. The relative frequency distributions are overlaid by the relative cumulative distributions.

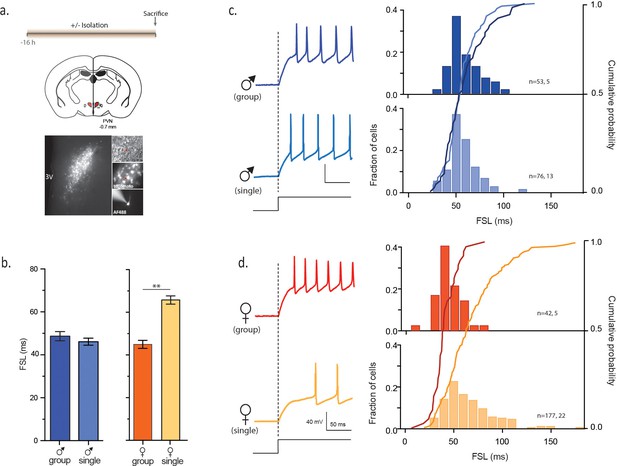

No sex differences in basal properties of CRH neurons.

(a) Left: Input resistance of individual cells from isolated males and females (male: 797 ± 32 MΩ, n = 157, vs female: 868 ± 23 MΩ, n = 273; unpaired t-test, p=0.06). Right: Spike thresholds of individual cells from isolated males and females (male: −51.5 ± 1.0 mV, n = 63 vs female: −51.3 ± 0.7 mV, n = 99; unpaired t-test, p=0.86).

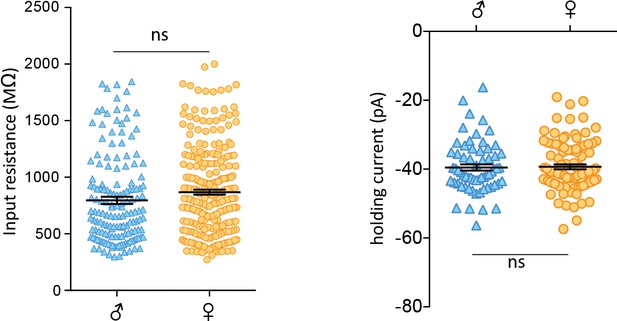

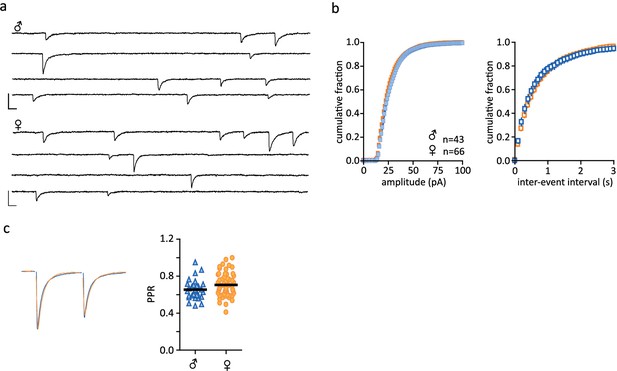

No sex differences in excitatory post-synaptic currents.

(a) Representative traces of spontaneous synaptic activity from individual cells from single-housed males and females with bath application of picrotoxin (100 µM). (b) Summarized data of cumulative fraction of amplitude (pA) and inter-event intervals. There were no significant differences in either the spontaneous amplitude (males: 34.14 ± 1.30pA, n = 12; females: 33.10 ± 1.19pA, n = 45, p>0.05) or frequency (males: 2.99 ± 0.61 Hz, n = 12; females: 2.50 ± 0.25 Hz, n = 45, p>0.05). (c) Peak scaled sample trace of a paired-pulse recording from a male (blue) and a female (orange). Right: Summary data of PPRs recorded from males and females. There was no significant difference in the paired pulse ratio (PPR) of EPSCs (males: 0.72 ± 0.05, n = 9; females: 0.80 ± 0.04, n = 32, p>0.05). Scale bars are 50 pA/10 ms.

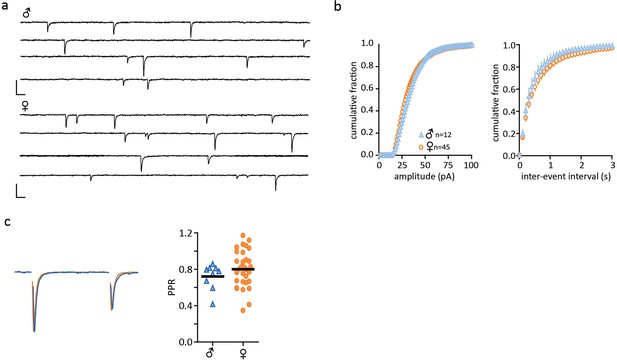

No sex differences in inhibitory post-synaptic currents.

(a) Representative traces of spontaneous synaptic activity from individual cells from males and females with bath application of DNQX (10 µM). (b) Summarized data of cumulative fraction of amplitude (pA) and inter-event intervals. There were no differences in sIPSC amplitude (males: 27.61 ± 0.89 pA, n = 43; females: 26.77 ± 0.76 pA, n = 66, p>0.05) or frequency (males: 2.25 ± 0.27 Hz, n = 43; females: 1.85 ± 0.14 Hz, n = 66, p>0.05). (c) Peak scaled sample trace of a paired-pulse recording from a male (blue) and a female (orange). Right: Summary data of PPRs recorded from males and females. There was no significant difference in the PPR of IPSCs (males: 0.65 ± 0.02, n = 29; females: 0.70 ± 0.02, n = 57, p>0.05. Scale bars are 50 pA/10 ms.

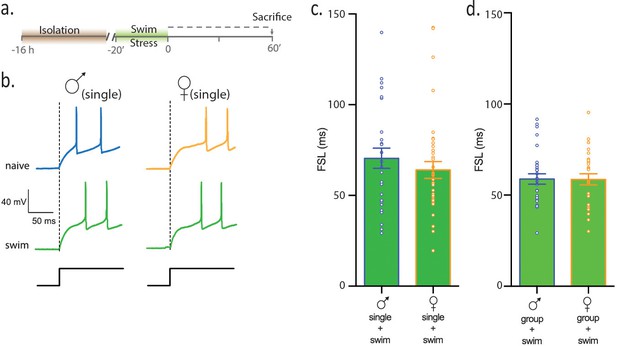

Females and males show equivalent sensitivity to an acute physical stress.

(a) Experimental timeline. (b) Neuronal responses to +80 pA depolarizing pulse in single-housed males and females. (c) Summary data show that following swim stress, FSL in single males and single females is not different (p>0.05). FSL in single males subjected to swim is significantly longer than FSL in naive single males (p<0.0001). FSL in single females subjected to swim is not different than single females (p>0.05). (d) Summary data show that FSL in group-housed males and females is not different (p>0.05). Group-housed males subjected to swim have longer FSL than group-housed, naive males (p<0.001) and group-housed females subjected to swim have longer FSL than group-housed, naive females (p=0.0001).

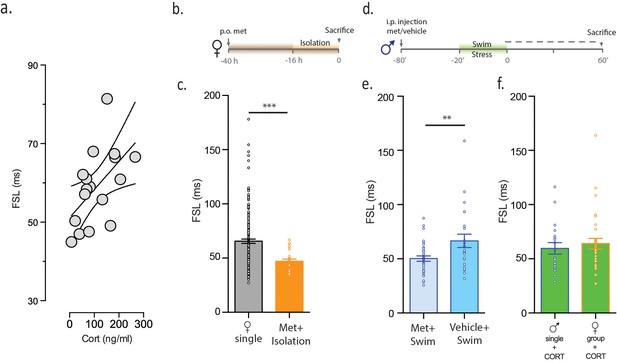

CORT is necessary and sufficient for increasing FSL.

(a) CORT measurements in male mice subjected to stress are plotted against FSL. (b) Experimental timeline. (c) FSL following pre-treatment with the CORT synthesis inhibitor metyrapone in drinking water prior to and during isolation in females (orange). The gray bar shows data from Figure 1 and is shown here for comparative purposes. (d) Experimental timeline. (e) Left bar shows FSL in male mice pretreated with Met prior to swim stress. Right bar shows FSL in male mice pretreated with vehicle prior to swim stress. (f) FSL is increased following incubation of slices from single males (p<0.021 vs malesingle) or group-housed females (p=0.002 vs femalegroup) with CORT. There is no significant difference in FSL between the two CORT-treated groups.

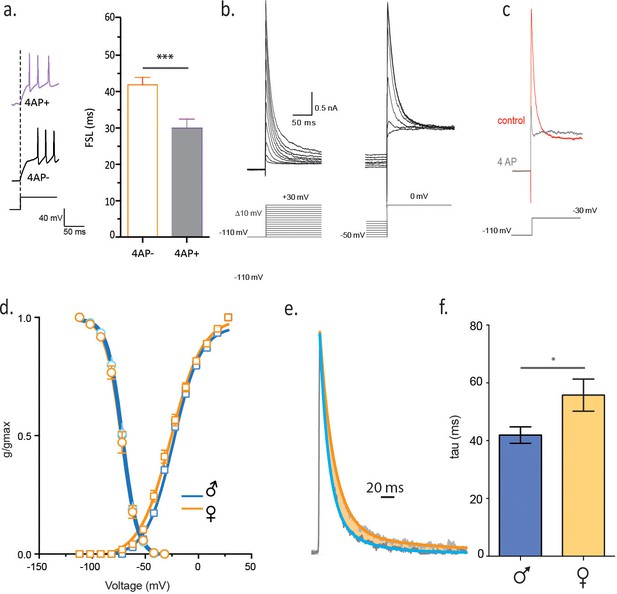

Slower decay of 4-AP sensitive, voltage-gated K current in isolated females.

(a) FSL is decreased by bath application of 2 mM 4-AP. (b) Voltage clamp traces from a male CRH neuron in response to different current step protocols as shown. (c) The rapidly activating and inactivating current was completely blocked by 6 mM 4AP. (d) The activation and inactivation curves are shown for single-housed females and males. (e) Currents at half-maximal activation, fit with a double-exponential are shown from males and females. (f) The slow inactivation time constant in malesingle and femalesingle is summarized (unpaired t-test, p=0.02).

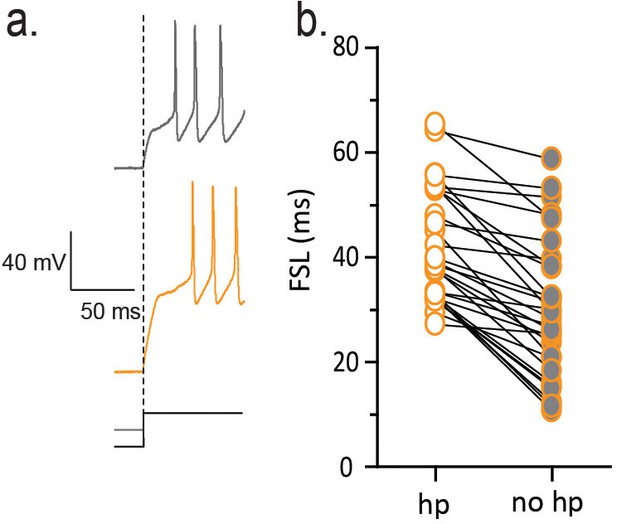

FSL is sensitive to membrane hyperpolarization prior to depolarization.

(a) Traces on left show voltage responses to a depolarizing current step with (orange) and without (gray) a hyperpolarizing pre-pulse. The absence of a hyperpolarizing pre-pulse decreases FSL as summarized in b (n = 29, p<0.01).

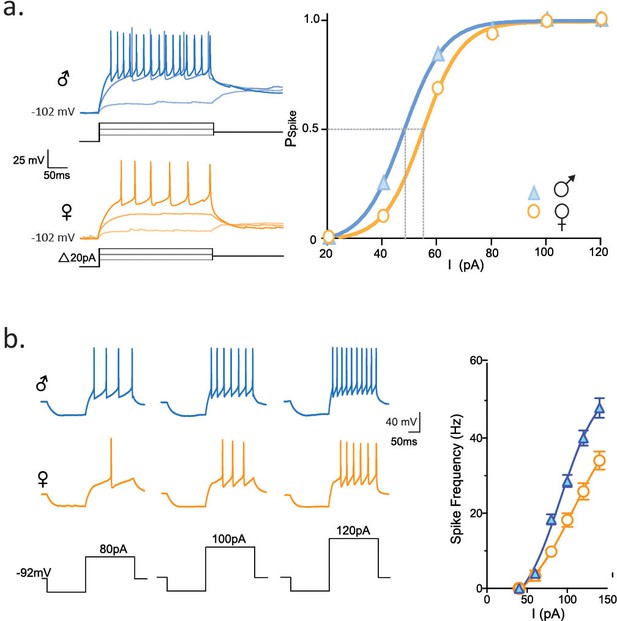

Longer FSL decreases spike probability and neuronal firing.

(a) Traces show firing properties of CRH neurons from individually housed male (blue) and female (orange) mice. Right panel shows the probability of eliciting a spike in response to varying current steps (K-S statistic, p<0.0001). (b) Responses from male and female CRH neurons to varying current steps. Right panel shows spike frequency in the first 50 ms of current step (K-S statistic, p<0.0001).