Totipotency: A developmental insurance policy

The very first decisions in the life of a mammal are made even before the embryo implants into the womb. During this time, as the number of cells in the embryo increases from one to two to four and so on, the cells start to specialize to form distinct lineages. The first choice a cell faces is whether to join a cell population called the inner cell mass and become part of the embryo, or to join the trophectoderm lineage and become part of the placenta.

The biology of this cell fate decision has been a subject of intrigue and experimental pursuit for over half a century. Building on landmark work by the late Krystof Tarkowski, Martin Johnson and others (Johnson and Ziomek, 1981; Tarkowski and Wróblewska, 1967), recent studies have demonstrated the importance of the Hippo signaling pathway – a pathway well known for regulating cell growth and death – in this process (reviewed in Sasaki, 2017). These studies have established how the polarity and position of a cell either cause activation of the Hippo pathway in the inner cells of the embryo, or inhibit it in the outer cells of the embryo to promote the expression of genes encoding a trophectoderm identity.

Previous attempts to determine the exact timing of when cells commit to either the inner cell mass (ICM) or the trophectoderm (TE) lineage yielded somewhat conflicting results. Now, in eLife, Janet Rossant and colleagues – including Eszter Posfai of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto as first author – report how they have used the thread and needle of fluorescent reporters and single-cell transcriptomics to stitch together classic and recent findings on this topic (Posfai et al., 2017).

A transcription factor called CDX2 has a central role in triggering the TE transcriptional program. The expression of CDX2 in cells that go on to become part of the TE relies on a complex called TEAD-YAP, which is activated by inhibition of the Hippo pathway in the outer cells of the embryo (Nishioka et al., 2009). Posfai et al. used a CDX2-GFP fusion (McDole and Zheng, 2012) to sort CDX2-positive and CDX2-negative cells, followed by single-cell RNA sequencing, to determine how the TE and ICM transcriptional programs became established as the embryo developed from the 16-cell stage to the 32-cell stage.

These data raise the question of what the progressive stabilization of cell fate might tell us about commitment to either lineage. Could the expression of TE genes restrict cells to a TE fate even when challenged experimentally (i.e., when placed in a new context)? In the assays used to test these questions, either single cells have to be implanted into genetically-distinct host embryos to generate a chimera, or an embryo needs to be rebuilt from isolated cells of one particular type (inner or outer). The contribution of daughter cells to the resulting embryo will reveal details about lineage commitment in the parental cells. With these techniques, the labs of Tarkowski, Johnson and Rossant previously established that both the inner and outer cells remain totipotent – that is, they can give rise to the ICM and TE lineages – until the 16-cell stage, with some inner cells remaining totipotent until the 32-cell stage (Suwińska et al., 2008; Rossant and Vijh, 1980; Ziomek et al., 1982).

Posfai et al. perform a contemporary version of these classic experiments using the CDX2-GFP fluorescent genetic marker, rather than cell position, to discriminate between prospective TE and ICM cells. They were able to precisely match cell fate commitment to the relevant gene expression profile of individual cells for both (GFP-positive and GFP-negative) populations at successive stages of development. This allowed them to confirm previous results and to paint a detailed picture of the molecular players that are potentially involved in stabilizing these two cell fates. For cells expressing CDX2, cell fate is basically sealed soon after blastocyst formation (at the 32-cell stage), and they are unable to give rise to the ICM. ICM cells, on the other hand, delay their commitment by an additional cell cycle, up until some point between the 32- and 64-cell stages (Figure 1). Posfai et al. confirm these results by genetically and pharmacologically modulating the activity of the Hippo pathway, which connects apico-basal cell polarity (or the lack of it in ICM cells) to gene expression.

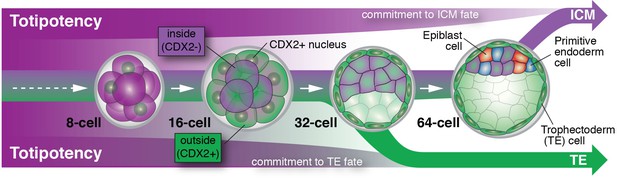

Cell differentiation in mammalian embryos.

Cells that develop into the trophectoderm (TE) express the transcription factor CDX2 (denoted here as CDX2+) and commit to their cell fate at around the 32-cell stage. Cells that will develop into the inner cell mass (ICM) keep their options open and only commit to their cell fate at a time between the 32- and 64-cell stage; these cells do not express CDX2 (denoted here as CDX2-). As embryos grow from the 32- to the 64-cell stage, ICM cells start to differentiate into two new cell lineages: the embryonic epiblast (future fetus) and the extra-embryonic primitive endoderm (future yolk sac).

This raises the question of why commitment to the ICM lineage takes place later during development. Perhaps it is no coincidence that ICM cells gradually begin to make their next cell fate choice during this time window. It is at this time that ICM cells make a decision to become epiblast (future fetus) versus primitive endoderm (future yolk sac). Therefore, the ICM may not be a cell fate per se, but rather a transitory state that lasts only until all the cells in the embryo have been allocated to one of the three lineages that make up the blastocyst. An asynchrony in making these early fate decisions could therefore reflect a developmental insurance policy: a strategy to guarantee that enough cells differentiate for each of the cell types that lay the foundation for all embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues (Saiz et al., 2016).

References

-

Roles and regulations of Hippo signaling during preimplantation mouse developmentDevelopment, Growth & Differentiation 59:12–20.https://doi.org/10.1111/dgd.12335

-

Development of blastomeres of mouse eggs isolated at the 4- and 8-cell stageJournal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology 18:155–180.

-

The developmental potential of mouse 16-cell blastomeresThe Journal of Experimental Zoology 221:345–355.https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.1402210310

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2017, Saiz et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 956

- views

-

- 167

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Chromosomes and Gene Expression

- Developmental Biology

Differentiation of female germline stem cells into a mature oocyte includes the expression of RNAs and proteins that drive early embryonic development in Drosophila. We have little insight into what activates the expression of these maternal factors. One candidate is the zinc-finger protein OVO. OVO is required for female germline viability and has been shown to positively regulate its own expression, as well as a downstream target, ovarian tumor, by binding to the transcriptional start site (TSS). To find additional OVO targets in the female germline and further elucidate OVO’s role in oocyte development, we performed ChIP-seq to determine genome-wide OVO occupancy, as well as RNA-seq comparing hypomorphic and wild type rescue ovo alleles. OVO preferentially binds in close proximity to target TSSs genome-wide, is associated with open chromatin, transcriptionally active histone marks, and OVO-dependent expression. Motif enrichment analysis on OVO ChIP peaks identified a 5’-TAACNGT-3’ OVO DNA binding motif spatially enriched near TSSs. However, the OVO DNA binding motif does not exhibit precise motif spacing relative to the TSS characteristic of RNA polymerase II complex binding core promoter elements. Integrated genomics analysis showed that 525 genes that are bound and increase in expression downstream of OVO are known to be essential maternally expressed genes. These include genes involved in anterior/posterior/germ plasm specification (bcd, exu, swa, osk, nos, aub, pgc, gcl), egg activation (png, plu, gnu, wisp, C(3)g, mtrm), translational regulation (cup, orb, bru1, me31B), and vitelline membrane formation (fs(1)N, fs(1)M3, clos). This suggests that OVO is a master transcriptional regulator of oocyte development and is responsible for the expression of structural components of the egg as well as maternally provided RNAs that are required for early embryonic development.

-

- Developmental Biology

Over the past several decades, a trend toward delayed childbirth has led to increases in parental age at the time of conception. Sperm epigenome undergoes age-dependent changes increasing risks of adverse conditions in offspring conceived by fathers of advanced age. The mechanism(s) linking paternal age with epigenetic changes in sperm remain unknown. The sperm epigenome is shaped in a compartment protected by the blood-testes barrier (BTB) known to deteriorate with age. Permeability of the BTB is regulated by the balance of two mTOR complexes in Sertoli cells where mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) promotes the opening of the BTB and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) promotes its integrity. We hypothesized that this balance is also responsible for age-dependent changes in the sperm epigenome. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed reproductive outcomes, including sperm DNA methylation in transgenic mice with Sertoli cell-specific suppression of mTORC1 (Rptor KO) or mTORC2 (Rictor KO). mTORC2 suppression accelerated aging of the sperm DNA methylome and resulted in a reproductive phenotype concordant with older age, including decreased testes weight and sperm counts, and increased percent of morphologically abnormal spermatozoa and mitochondrial DNA copy number. Suppression of mTORC1 resulted in the shift of DNA methylome in sperm opposite to the shift associated with physiological aging – sperm DNA methylome rejuvenation and mild changes in sperm parameters. These results demonstrate for the first time that the balance of mTOR complexes in Sertoli cells regulates the rate of sperm epigenetic aging. Thus, mTOR pathway in Sertoli cells may be used as a novel target of therapeutic interventions to rejuvenate the sperm epigenome in advanced-age fathers.