NADPH oxidase mediates microtubule alterations and diaphragm dysfunction in dystrophic mice

Figures

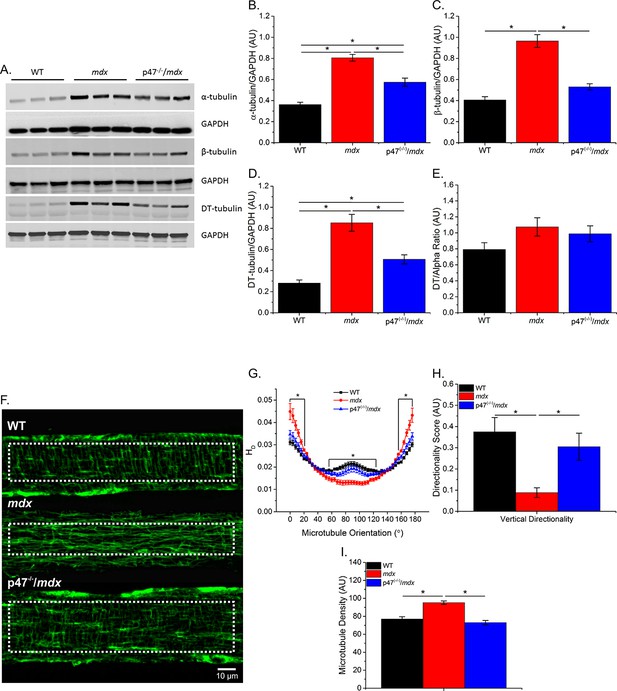

Eliminating Nox 2 ROS production prevents alterations in tubulin content and the microtubule network.

(A) Representative western blot images of α-, β-, and DT-tubulin content in all three genotypes. (B–D) Eliminating Nox2 ROS production decreases absolute α-, β- and DT-tubulin content in dystrophic diaphragm muscle. (E) The relative amount of DT-/α-tubulin is not different between groups. (F) Representative images of diaphragm myofibers stained with α-tubulin. (G–I) The lack of Nox 2 ROS prevents microtubule disorganization and the increase in microtubule density seen in mdx muscle. p≤0.05 *Significant difference between groups in at least (A–E) nanimals = 6 and (F–I) nanimals = 3 and nfibers = 15.

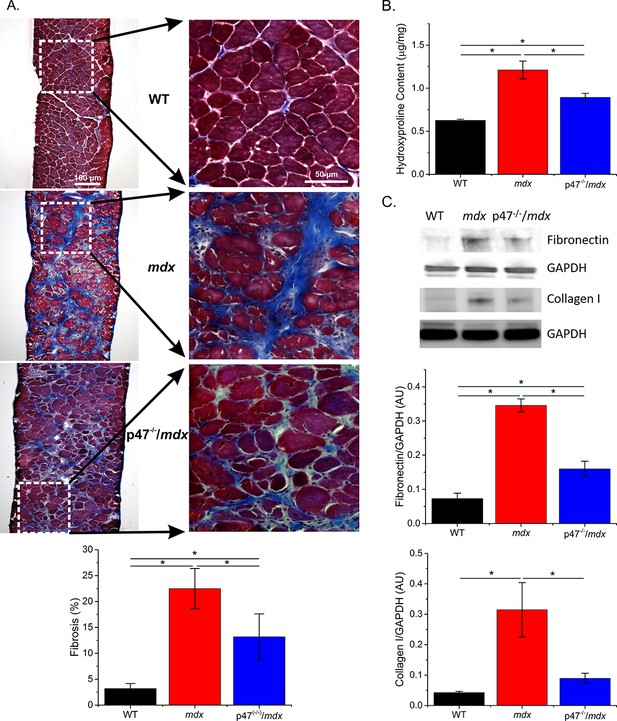

Genetic deletion of Nox2 ROS production reduced fibrosis.

(A) Representative trichrome images of fibrosis in all three genotypes. Eliminating Nox2 ROS production in dystrophic muscle reduced fibrosis compared with mdx mice. (B) Hydroxyproline levels were elevated in dystrophic muscle and eliminating Nox2 ROS reduced hydroxyproline content compared with mdx mice. (C) Representative western blot images for fibronectin and collagen I content in all three genotypes. Fibronectin and collagen I content were elevated in mdx diaphragm and eliminating Nox2 ROS reduced both toward WT levels. p≤0.05 * Significant difference between groups in at least nanimals = 6 for trichrome and hydroxyproline and nanimals = 3 for fibronectin and collagen I.

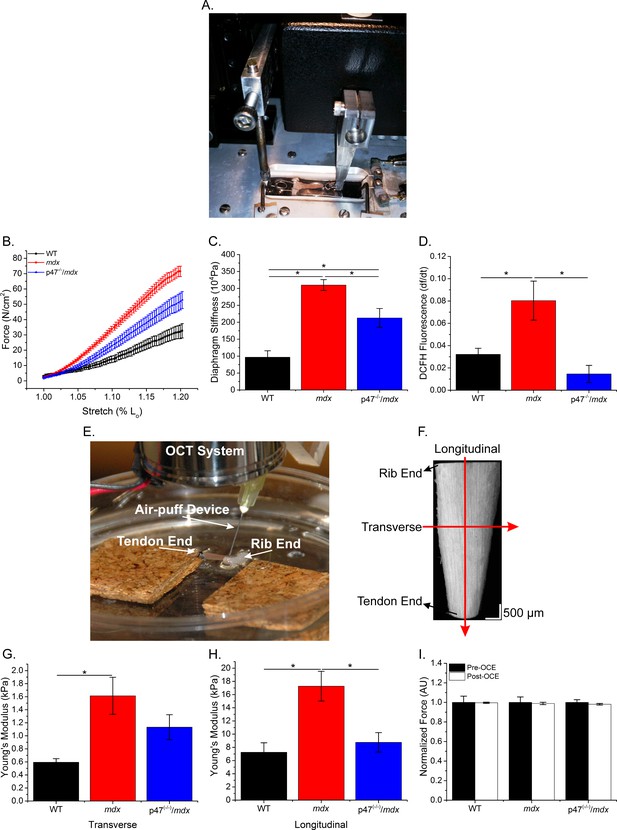

The lack of Nox2 ROS reduces muscle stiffness and stretch-induced ROS.

(A) Image of the passive stretch experimental set-up. (B) Average passive diaphragm force recorded during stretch for each genotype. (C) Eliminating Nox2 ROS production reduced diaphragm tissue stiffness. (D) Stretch induced ROS in mdx muscle was elevated above WT levels and eliminated in p47-/-/mdx diaphragm. (E) Image of the OCE experimental set-up. (F) Representative OCT image of the diaphragm taken prior to OCE experiments. (G) Transverse diaphragm muscle stiffness increased in mdx compared with WT mice; eliminating Nox2 ROS resulted in a decrease toward WT (p=0.09). (H) Genetic inhibition of Nox2 ROS reduced longitudinal diaphragm stiffness to WT values. (I) Muscle function was not altered following OCE measurements. p≤0.05 *Significant difference between groups in at least nanimals = 6 per group.

Longitudinal.

Following the application of the air puff (<1 ms in duration), the displacement of the diaphragm tissue was monitored as the wave propagated down longitudinal axis while imaged at 62.5 kHz with OCE. Visualization is 5000 times slower than the actual speed.

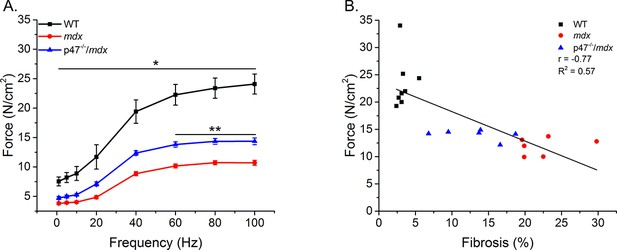

Eliminating Nox2 ROS protects against muscle and respiratory dysfunction.

(A) WT was significantly different from mdx and p47-/-/mdx animals at all stimulation frequencies. The p47-/-/mdx animals were different from mdx at 60–100 Hz and trended toward significance at 40 Hz (p=0.098). (B) Fibrosis significantly correlated with muscle force. p≤0.05 *Significant difference between groups in at least nanimals = 6.

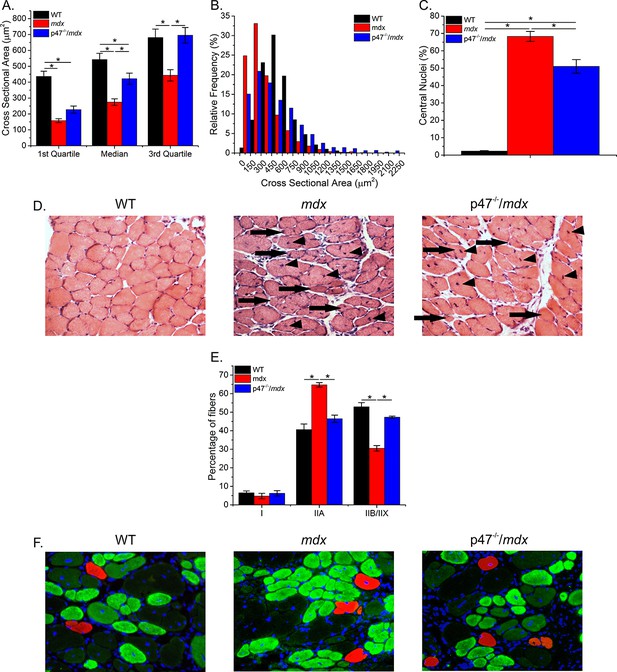

Eliminating Nox2 ROS protects against phenotypic alterations in dystrophic diaphragm muscle.

(A–B) Eliminating Nox2 ROS increased median cross sectional area compared with mdx diaphragm. (C) In dystrophic diaphragm lacking Nox2 ROS production the number of centralized nuclei were reduced compared with mdx diaphragm tissue. (D) Representative hematoxylin and eosin stained images of diaphragm cross-section showing central nuclei (arrow head) and smaller fibers (arrow). (E) Fiber type distribution was maintained by eliminating Nox2 ROS production in dystrophic diaphragm muscle. (F) Representative immunofluorescently labeled diaphragm cross-sectional images showing fiber type distribution. Type I (red), IIA (green), IIB/IIX (white x, unstained and viewed from bright field overlay). p≤0.05 *Significant difference between groups in at least nanimals = 3.

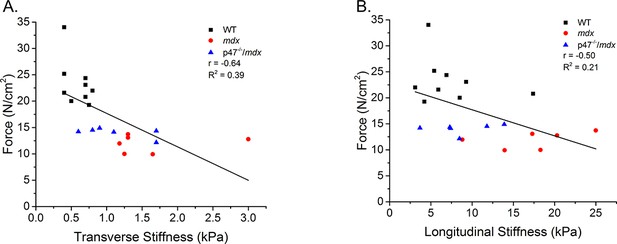

Linear correlation of stiffness measured by OCE and the peak force.

There was a significant correlation between peak force and transverse as well as peak force and longitudinal diaphragm stiffness.

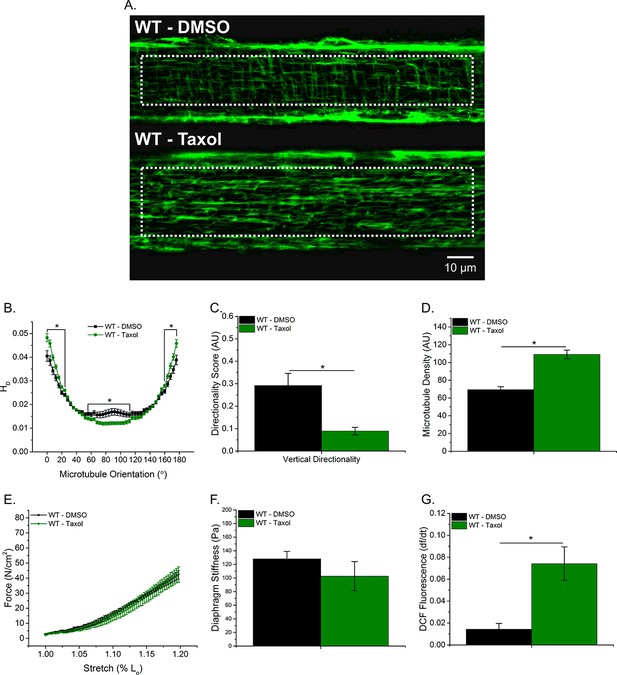

Taxol-induced MT polymerization has no effect on tissue stiffness but induced ROS production.

(A) Representative images of MT network in control (DMSO) and Taxol-treated diaphragm (20 μM for 2 hr). (B–D) Taxol induced MT disorganization and increased microtubule density compared with control. (E) Average passive diaphragm force recorded during stretch was not affected by Taxol. (F) Polymerizing the MT network had no effect on diaphragm tissue stiffness. (G) MT network polymerization enhanced stretch-induced ROS in Taxol-treated diaphragm. p≤0.05 *Significant difference between groups in at least (A–D) nanimals = 3 and nfibers = 15 and (E–G) nanimals = 5.

Tables

Tubulin and stiffness correlations.

| Adj R2 | Fibrosis | α-tubulin | β-tubulin | DT-tubulin | DT-/α-tubulin | MLR (fibrosis/DT) | MLR (fibrosis/ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transverse | 0.69 * | 0.46 * | 0.51 * | 0.51 * | 0.10 | 0.69 | 0.67 |

| Longitudinal | 0.44 * | 0.20 * | 0.40 * | 0.41 * | 0.19 * | 0.44 | 0.49 |

-

Most variables significantly correlated with both transverse and longitudinal stiffness. MLR revealed fibrosis accounted for the majority of the variance observed in either stiffness measure. p≤0.05 *Significant correlation in at least nanimals = 6.

Force and stiffness correlations

| Adj R2 | Fibrosis | MLR (fibrosis/trans) | MLR (fibrosis/long) | MLR (fibrosis/long/trans) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.49 |

-

MLR revealed fibrosis accounted for a majority of the variance observed in diaphragm muscle function. p≤0.05 *Significant difference between groups in at least nanimals = 6.